Greetings from Philadelphia, where we just might make it through this winter after all, as evidenced by the fact that the high this week will be 58° and the Eagles won the Super Bowl.

If you know me, you know I genuinely hate football; I hate the toxic masculinity, the traumatic brain injuries, the celebrity worship. I also don’t understand it, as in, I struggle to follow the game play: after the Thanksgiving dinners and Sunday suppers of my childhood, when the men filed into the living room and plopped down on sofas and chairs with sighs and grunts, and the women loaded the dishwasher and made the coffee and plated the pie, I tried to conjure excitement as my dad banged his fist on the coffee table and yelled “GO GO GO GO GOOOOOOOOOO GET EM!” as a man in a helmet flung himself across a wide green field, impossibly fast, bodies hurling themselves into his path, piling in his wake. But no matter how hard I tried, or how many people tried to explain it to me, the figures scrambling on the screen would never coalesce into any kind of meaningful pattern, and this became yet another way I didn’t—couldn’t—fit in.

Going to college in a Southern town as an art kid/wierdo in the 90’s meant resisting the pervasive culture of fraternities and sororities, which was perfectly encapsulated and exemplified by the rites and rituals of football. Both of my brothers were in fraternities; I wanted nothing to do with it. In my five years living in Athens, Georgia, I vowed to never set foot in Sanford Stadium, and I never did, spending my game days instead serving pitchers of beer to the slobbering, sunburnt, belligerent patrons at every restaurant job I ever had (and later, delivering them pizza; more on that in the essay below).

5. Comets Section.

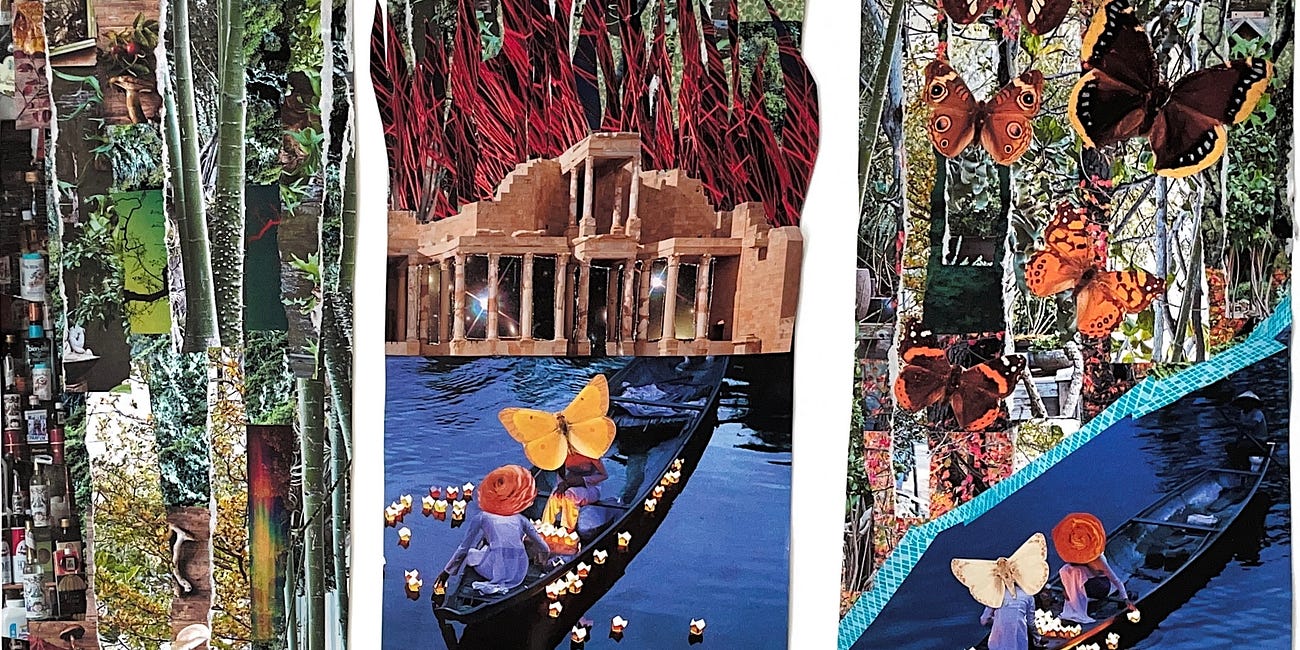

I’ve been trying to finish this collage for months. The piles of paper, wood, glue, glitter, bins of markers, x-acto knives, and magazines have been cluttering my desk, the thing half done. This morning I finally finished it, cut it up, rearranged it, shoved the art supp…

But if you know me, you also know that there is nothing I love more than a communal spiritual experience. And if you, too, live for moments of shared transcendence, then you also know that we spiritual seekers don’t get to pick and choose the hour or the day when these moments arrive at our doorstep: sometimes the moment of bliss arrives, like a thief in the night, in the form of… football.

Or more specifically, a town imbued with supernatural reverence for a particular football team, a team that transcends football to encompass an ethos of resilience, defiance, and collective joy against the odds, a town called Philly and a team called the Eagles (below, an essay from the last time the Eagles went to the Super Bowl).

6. What we talk about when we talk about therapy.

It’s a strange thing to arrive at a place you’ve been trying to get to.

On the morning of the Eagles parade, which was also Valentine’s Day, on my way to work, the city was abuzz, public transit was free thanks to a generous donation from Kevin Hart’s tequila brand, and the bus was packed like sardines because many of the subway stations were closed for crowd control. My woolen winter coat blazed red in a sea of green, and I participated in the spontaneous chants of E-A-G-L-E-S EAGLES! The glee was contagious, until I heard one lone voice behind me state matter-of-factly, I don’t like football. The proverbial record screeched, and all heads swiveled to see the offender.

I just don’t like sports, man, the lone dissenter said, shrugging his shoulders.

I don’t like boxing either, he continued, adding insult to injury. Who wants to see a man punching another man? Not me.

The crowd was silent, the tension thick. Then a nearby passenger said, almost to himself, boxing is a beautiful sport, man. And that seemed to settle it.

On parade day, schools and businesses closed, and MORE THAN A MILLION PEOPLE flooded Center City to greet the conquering warriors in what can only be described as a modern-day Roman Triumph. The players formed a victory procession down the Ben Franklin Parkway towards our most prominent public building, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is essentially a massive Roman temple, with soaring columns and a giant gilded statue to the goddess Diana. I love this city, ancient and haunted, bedeviled by the old rites.

It turns out, Philly is my Roman Empire.

Or maybe I just have Empire on the mind.

Like every person of conscience at this moment, I’m trying to figure out the best use of my energy, a way forward through the collapse and dismantling of our government and society as we know it. I don’t know the answer, because the answer will be different for each person, on each day, but I hope we can free ourselves from the burden of trying to save institutions that can never be repaired or reformed, and put ourselves about the work of building living ecosystems of mutual care and belonging in our daily lives, now, in the places where we are.

I hope we can make the connections between what is happening now and the COVID pandemic, how we have been desensitized to mass death and suffering by abject neglect and abandonment of the social contract. I hope we can make the connections between what is happening now and what we have allowed to happen to occupied Palestine for the last eighteen months plus a hundred years, how the proverbial chickens are coming home to roost (more on that from Noura Erakat in

: The Boomerang Comes Back: How the U.S.-backed war on Palestine is expanding authoritarianism at home—from Project Esther to violence at the border).I’m not interested in I-told-you-so’s, but I don’t want to forget. I did a lot of forgetting in the Obama years, allowing the illusion of safety and the promise of a slightly more robust social safety net and symbolic gestures of progressive inclusion sedate me into selectively not seeing the global collateral carnage of our American way of life, of wanting so badly to believe that if we just took it slow, and kept it safe, and planted our gardens, and improved school lunches, that the long arc of the moral universe would bend towards justice by itself, eventually (to paraphrase some things

said at her talk in Germantown this past Friday for her new book, Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism).As

said (and many others have said in their own ways), I want y’all to ask yourselves, and encourage everyone around you to ask, every time you come across a criticism of the Trump administration: what is being mourned or rejected here? Is it Trump’s destruction of due process and balanced government—eroding the health of the State; is it obstructing the free flow of capital and commodities—potentially hurting business; or is it directly going after and harming marginalized people?We really have to do the work of distinguishing between harm done to people and harm done to institutions and systems that are actually inherently harmful (I’m linking lots of articles I find helpful in regards to this question of how to respond or react to the blitz/onslaught/flooding the zone here on my notes page).

As for me, I have been heeding the advice of many wise people to find a movement home, to actually organize. I have committed to Writers Against the War on Gaza (WAWOG) as my movement home, have recommitted to making all the meetings, and I’ve been working to distribute print copies of The New York War Crimes, which I talked about at greater length at the end of my last letter.

I’ve also been heeding the advice of many wise people and studying. During January and February I participated in an online study group of the book Psychoanalysis Under Occupation by Lara Sheehi and Stephen Sheehi hosted by the USA-Palestine Mental Health Network. I never thought of myself as a psychoanalysis guy, but it turns out, wonder of wonders, I didn’t actually know much about psychoanalysis.

The book is described thusly:

Heavily influenced by Frantz Fanon and critically engaging the theories of decoloniality and liberatory psychoanalysis, Lara Sheehi and Stephen Sheehi platform the lives, perspectives, and insights of psychoanalytically inflected Palestinian psychologists, psychiatrists, and other mental health professionals, centering the stories that non-clinical Palestinians have entrusted to them over four years of community engagement with clinicians throughout historic Palestine.

There are so many enriching learnings to be gleaned from this book, and the practice of meeting weekly and learning together with a small group of therapists from around the world was deeply nourishing, but what stands out for me most prominently again and always is the conviction/commitment (iltizam) of the Palestinian people. As the Sheehis state in their epilogue entitled Resistance Keeps Us Sane:

These reference points (sumud/steadfastness, iltizam/commitment, mas’uliyah/responsibility, al-tahaquq/self-realization) make life legible, manageable, and livable. They allow Palestinians to see the psychopathy of settler-colonial logic…. to maintain an “intact ego” which itself is the kernel of Palestinian ontology that Zionism so desperately seeks to erase.

I want to be worthy of this world. I want to be a person of conviction.

So when I get home from sitting with my friend in the hospital1, and it’s too late to take the car to Swarthmore to catch Ta-Nehisi Coates talking about his new book The Message, I go anyway, in hopes of catching the tail end and handing out some papers.

I do not want to do this.

I do not want to drive forty minutes to carry a hundred newspapers on my already-injured shoulder too far through a construction site because I can’t find parking and I can’t find the entrance just to stand out in the freezing cold, looking like a fool, pushing papers into college students’ hands like a zealot. I want to stay home, pop an edible, watch Celebrity Jeopardy, and eat soup.

But I go, because nothing changes if nothing changes. I arrive an hour late, really fuck up my shoulder schlepping the papers, and sit in the lobby with the student ushers, watching the Q & A with Coates on a TV monitor. He talks about moral courage, and how all the education and academic degrees in the world are useless if they are used to justify immoral and inhumane actions, which is what they are mostly used for. Intellectual pursuits should lead us to a greater morality, a greater humanity, he says, to vigorous nods from my comrades in the lobby.

The event ends, and I run outside with my hundred papers, and shove them into people’s hands as they flood out of the auditorium. Some people are reticent, or confused, but most people are excited, grateful, come back for more to give away. I go through all hundred papers in less than ten minutes.

Nine days later, Swarthmore Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) occupied an administrative building on campus for eleven hours, protesting disciplinary charges related to demonstrations and encampments for Palestine during the 2023-24 academic year and demanding the college’s divestment from companies linked to Israel (via the Swarthmore Phoenix), and my actions are braided together with their actions, which are braided together with Coates’ actions, which are braided together with the sumud and conviction of the Palestinian people.

Twenty-five years ago, when Duncan and I arrived on the scene in Asheville, North Carolina (and it definitely was a scene, a convergence point for Southern punx and anarchists at the dawn of the post-9/11 world, on the cusp of the second Gulf War), we plugged in to working with the Asheville Global Report, an independent print newspaper aggregating underreported global news and generating local content. We volunteered on a delivery route, we proofread the galleys, we helped out with fundraisers.

In 2005, we had a baby, which coincided with the end of that era of Asheville organizing. The external pressure of gentrification and repression closed down our community spaces; the internal pressure of infighting and human frailty drove us away from each other. People scattered. Lots of people moved away; others, like me, moved into their own worlds, trying to make a living and keep their heads above water.

The business I started, Short Street Cakes, was born in that moment, along with my son. I love the Cake Shop. I miss it all.

In the depths of my many years of back-breaking, balls-to-the-wall, incessant, and relentless work, worry, fatigue, heartbreak, and insanity that is owner-operating a business, specifically a brick-and-mortar food business, specifically a brick-and-mortar food business in the wedding industry—when people would ask me how I was doing, I would say, sometime maniacally, sometimes happily: JUST LIVING THE DREAM!

I learned that you can’t say that you’re tired, or busy, or need a break, because people will admonish you to be more thankful for your success. Good problem to have! they will insist, and I would try to be gracious, even while my success was quite literally killing me.

As much as I loved it, as much as I miss it, as much as the Cake Shop shaped me and gave me a way of being in the world that saved me, a lifeboat to the other shore, the Cake Shop was never my dream.

There are many people who dreamed all their lives of owning a bakery. I was not one of them. I loved making beautiful things, I loved working with amazing people, but I never wanted to process payroll or create a profile on WeddingWire or manage relations with the oven repair guy.

My dream was to be an activist.

My heroes were Dorothy Day and Toni Morrison and Thomas Merton and Emma Goldman, writers and revolutionaries. I didn’t want to do monthly inventory, I wanted to do protests and lectures and radical newspapers and Stonewall marches and make new friends from big cities in other countries and take part in the conversation that spans the ages about what constitutes love and meaning. I wanted to take a fucking risk for humanity.

And so, in collaboration with a younger version of myself, striving to make her proud, and with the sumud and conviction of the Palestinian people as my North Star, I’m finding my way, finding my work in the world, in this moment. In the words of another radical hero ancestor, Audre Lorde:

To refuse to participate in the shaping of our future is to give it up. Do not be misled into passivity either by false security (they don’t mean me) or by despair (there’s nothing we can do). Each of us must find our work and do it.

May you find the conviction to do the work which is yours, and yours alone, to do.

In love and solidarity,

⚔️❤️,

Jodi

Home + The World is an occasional newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake.

Home + the World observes the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, and Jodi Rhoden is a proud signatory of the Writers Against the War on Gaza statement of solidarity with the people of Palestine.

Visit Home + the World on Bookshop.org, where I’m cataloging my recommended reading in the genres of memoir, fiction, and—of course—healing, self-help, and social justice. If you purchase a book through my shop, I will receive a commission and so will an independent bookstore of your choice. Find it here!

⚔️❤️ Jodi

Some of you may know my friend, legendary tattoo artist Kerry Burke. She and her daughter Bella were our neighbors in Asheville when Bella was just a baby; they now live in Philly, and Kerry is undergoing treatment for gastric cancer. Here is the gofundme if you are able to contribute, and the meal train if you are able to bring food or send a gift card for takeout.

There she is! I squealed when it came into my inbox this morning. <3

So, so happy to know you, friend ✨🔥✨ What a gem. And a big thanks for the recorded version!