I’d rather be happy than right.

One of my mother’s favorite mottos, I’d rather be happy than right was ostensibly meant to convey her plucky outlook on life: that she would rather take the high road and acquiesce in an argument than to disturb the peace by insisting on a position, a concept which is 1) historically untrue of my mother and 2) actually a horrible piece of advice, one that confounded me as a child.

Who would be made happy by lying? I would think to myself. Who would be satisfied allowing some falsehood to prevail in the name of peace? And why are those the only two choices? Who decided that those who are correct must, then, necessarily, be unhappy?

I’d rather be happy than right is transactional. I’d rather be happy than right says: I can’t be loved and stand in my truth at the same time, so I will stop telling the truth so that you will no longer be angry at me.

I’d rather be happy than right says: I will trade in my authenticity for connection.

Some images of war stay with you longer than others.

Recently, for me, there were two: first, the image of three cops on top of one Black protestor at the anti-war encampment at Emory University in Atlanta, the cops tasing the protestor repeatedly in the stomach, then smashing the protestor’s face down in the dirt, and cuffing their hands behind their back. Once the person was totally subdued (on their stomach, in the dirt, hands cuffed behind their back) the cops continued tasing them over and over and over again, in the back, in the kidney, in the thigh. Later I learned that the victim was wearing the clearly visible insignia of a medic.

The other video that haunted me, made my heart race and disgust rise in my throat, was the one of the white frat boy at Ole Miss taunting a Black anti-war protester, employing racist tropes by aggressively jumping up and down and making monkey noises and faces.

I didn’t want to be writing about this. When I started this newsletter at the beginning of last year, I did not intend it to be political, except in the way that the personal is political, which is to say that I intended this newsletter to be personal. I wanted to write about sobriety, about healing, about therapy. If I’m being honest, I thought of myself at that point in my life as post-political.

But the behavior of these white men, these police, these soldiers, is personal to me because I was raised by them. They are my people, the ones I left behind. My trauma, my addiction, my healing, is intertwined with them, with this.

Atlanta is where I was born, into the burgeoning world that white flight built, on the cusp of a New South, on the cusp of a new world. But there is nothing new under the sun.

Ole Miss is where my brother went to school, where he joined a fraternity that venerates the confederacy, a fraternity that holds a formal ball every year where the members and their dates overtly cosplay antebellum enslavers, even going so far as to hire all-Black service staff for the event.

Atlanta is where my brother is a volunteer sheriff’s deputy, on his weekends off from being a real estate developer. Was he there at Cop City when Tortuguita was killed?

Atlanta is where my father had a gun room, a locked basement gallery with hundreds of weapons and stockpiles of ammunition. He told me once when I was in high school that his worst fear was that the hoards and mobs of angry Black and Muslim people in the city would finally rise up and attack us in our peaceful suburbs. That he had these guns to protect us.

In the hands of the cops at Emory, in the eyes of the gleeful cruelty of the white mob at Ole Miss, I see the men in my family, clearly, unmistakably.

But what of the women?

Well, the women, you see, they would rather be happy than right.

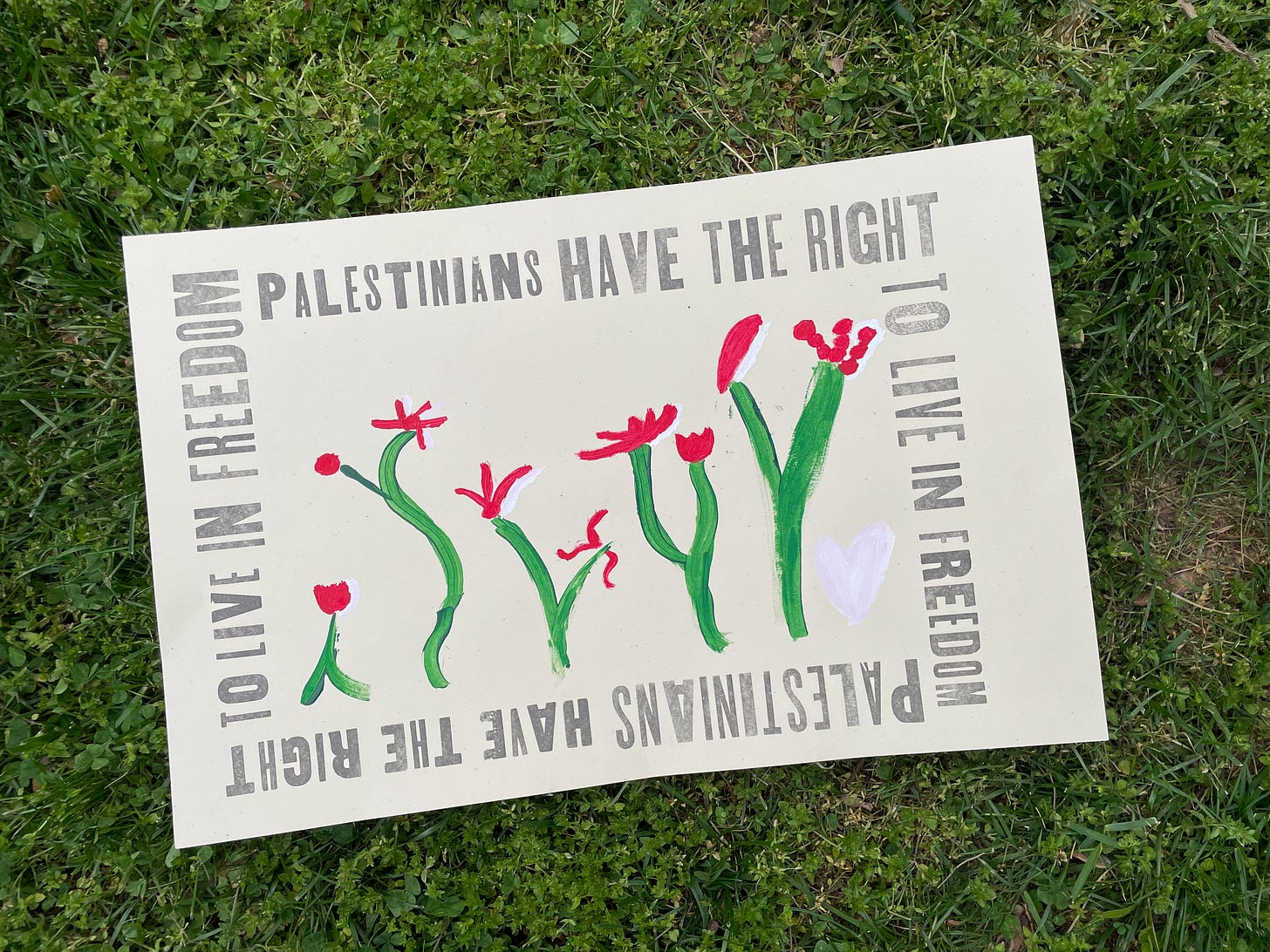

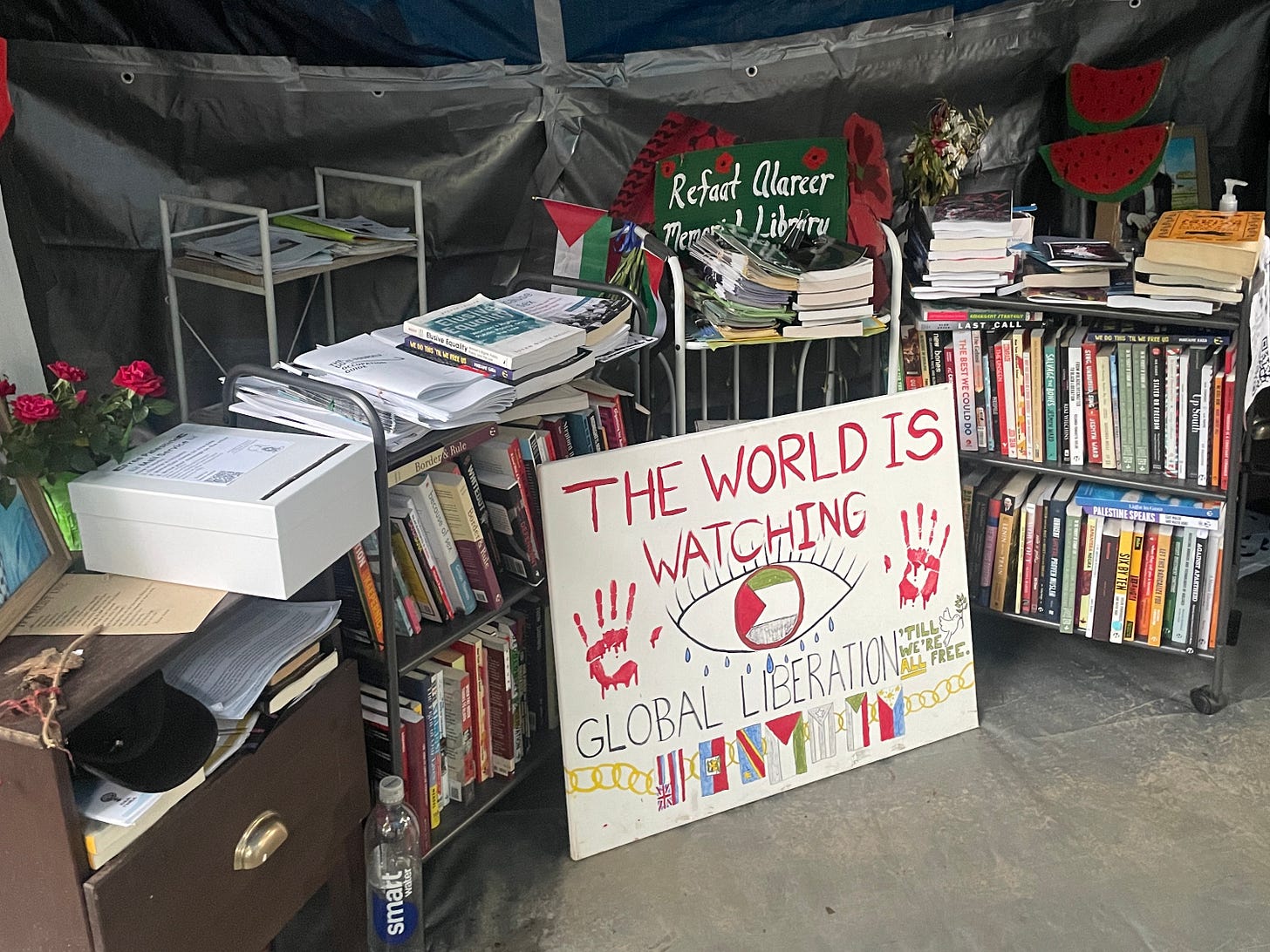

On Monday night, I went back to the Penn encampment for a rally, and to see Marc Lamont Hill speak. In the few days since I had been to camp, it had grown: in numbers, yes, but also in organization, in resources. The Refaat Alareer Memorial Library has grown, and now has a structure over it with tarps to protect it from the rain. The medic tent now has solar panels for people to charge their phones. There is now a wellness tent, where I am one of many mental health professionals signed up for shifts to offer crisis and emotional support to students in the encampment. The camp is clean, the food is plentiful, and systems of sanitation, laundry, and, education are in place.1

In short, in 13 days, the encampment has created a model and a microcosm of the world as it could be, as I believe it would be, if our kith and kin were not systematically prevented from following our natural inclinations to tend, to attune, to bond, to nurture, to heal, to make art and food and music and dance and sing; to live and die in dignity.

I feel so safe in the encampment.2 I recognize people, they recognize me, I see the way they behave in the high-stress, potentially violent situations created by police, and I trust them. I see their principled strength and it makes me feel loved and protected in a way that my father’s guns never did, because there is a difference between being protected as a person and being protected as a possession.

On Monday, at camp, a friend introduced me to another friend who has been sleeping in the encampment for 10 days. Do you need anything? I asked. She looked into the middle distance, thinking, then replied, honestly, no. Every time I think of something I might need, somebody walks up to me with it in their hands. It’s like magic.

What if, rather than having to choose between being happy or being right, we could be something else entirely? Something unknown, something messy, something that looks like love and feels like life?

Because, even while the bombs rain down and webs of lies are woven, life does not stop singing life’s song.

Somebody in Madison County found their dog after 5 days gone.

The singer in the black metal band got engaged in the parking lot of the Acme grocery store.

Somebody’s lover in a blue room on a Sunday afternoon brought her to the shores of an orgasm so deep and profound that it became a portal, the waves of it welling up in her eyes and breaking as she laid in his arms and sobbed and came, her salt tears baptizing so many years of grief.

Somebody, somewhere, swam out to a floating dock in the dark, and, reaching it, laid on their back and marveled at the vastness of the Milky Way, and, to their great relief, felt themselves as so very, very minuscule in the scope of time and space.

Somebody, somewhere, saw the God light pouring onto the ninth hole and changed his mind.

Today the moon is made new in Taurus (the moon loves to be in Taurus). New moons provide a symbolic vessel in which to consciously release what is ending, and plant the seeds of what is to come: from the mundane, to the mystical, to the world-historic. So let us let it go. Let us let go of the world that allows all this evil. We built this world, we can build another.

May we compost all that is godforsaken and rotten, may we divest from every broken plank and rusty chain, may we steward its downfall, may we hasten its demise. May we transmute it into something holy: the good black soil that grows the fruit that nurtures the world that is, right now—as we live and breathe—struggling to be born within us.

Home + The World is a weekly newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. All content is free; the paid subscriber option is a tip jar. If you wish to support my writing with a one-time donation, you may do so on Venmo @Jodi-Rhoden. Sharing

with someone you think would enjoy it is also a great way to support the project! Thank you for being here and thank you for being you. ⚔️❤️ JodiIt bears repeating here, that the camp exists for the purpose of pressuring the University of Pennsylvania to 1) disclose its financial ties to Israel’s apartheid regime, 2) divest from the same, and 3) defend the rights and lives of Palestinian students and those speaking out against the genocide of Palestinians. No waxing poetic about the beauty of life in the encampment should overshadow this purpose: to stand in solidarity with Gaza, to shine a light on Gaza, to stop the war on Gaza, to stop the genocide of Palestinians, to stop the horrific occupation of Palestine by a violent and racist settler-colonial regime.

I am also no longer dignifying the overtly disingenuous accusations of these encampments and this anti-war movement as antisemitic by continuing to try to provide evidence to prove that they are not. Accusations of antisemitism are plainly in bad faith, as even the smallest amount of investigation into who is actually leading, organizing, and participating in the protests and what the camps and protests are actually like will readily reveal. Antisemitism is real and growing, but it is not coming from the pro-Palestine, anti-war, anti-genocide movement. It is coming, as always, from right-wing fascists, who are now leveraging Zionism for their own bizarre ends.

Another absolutely beautiful piece. Reading your origin story and tying it into the person who are today was moving and so relatable to many. So many of us are finding community during these dark times which is a shred of light in all this madness. Thank you for your sharing and your vulnerability.

A beautiful, spiritually written essay. Full of new life vision. It’s hard to tell your truth when others only sense their own pain and not yours. I told someone how I was feeling about how I was treated by them. The person, my adult daughter, felt betrayed by me for expressing or even having this feeling. I sense this is what is happening in the body politic. What you are sharing is entering a tent where there is a shared belief at the threshold. We can see a way to live with one another that embraces a paradigm of cooperation rather than isolation.