Is there anything else you want to make sure we talk about today? I ask her the question I ask at the end of every session. After an hour of talking about her grief, her recovery, her pain, she says:

Actually, yes, I’ve been meaning to tell you, I’ve been trying to befriend a crow.

She goes on to tell me, with joy and wonder, about her garden, about the peppers and the tomatoes and learning to overwinter the kale, and her birdfeeder—the bluejays and cardinals and squirrels and chickadees and crows and the relations between them all—a microcosm of the universe, on the back deck of a rowhouse on Baltimore Ave.

She tells me how there’s this one particular crow she’s got her sights on, she says, he’s been around, and she feels like if she can befriend him, maybe he will tell the others, and then she could befriend a whole murder of crows! Just think of it! That’s it; that’s the one last thing she wanted to make sure I knew. After all she’s been through (use your imagination), this is what she wants to talk about, to live into: the peace of wild things. A friendship with a crow.

I became a therapist for this; for these small, sacred moments of clarity and connection. For the joy. I became a therapist in hopes that in these relationships, that in these small, sacred containers of trust and positive regard and restoration and repair there could be a small, sacred way to be a part of healing the world, and healing my own broken heart, too.

I also became a therapist because I thought I was done being an activist.

In my old life, in Asheville, North Carolina, before we up and moved our family to Philly in 2020, that whole sweeping year of quitting—I had became exhausted and demoralized at the way people in my “social justice community” were treating one another: the cancellations, the smear campaigns, the fealty tests, all the shunning and shaming and posturing and the transactional, conditional relationships; the abuse and control masquerading as justice, as righteousness, as right thinking and right action. It all started to feel very fundamentalist, very communal-narcissist, and actually quite cultish. I had come to understand that, by trying to protect ourselves and others from harm, we had unwittingly created the same dynamics we were trying to free ourselves from. It was a hall of mirrors, and I was a part of it, and I was totally complicit. So I quit.1

I decided to go back to graduate school to become a therapist. No amount of activism will heal the world if we don’t heal our trauma first, I thought to myself. And I shifted my focus from the outer world to the inner one: starting from inside myself. We are murmurations, I now knew. Our lives ripple out from the most subtle inner movements, I understood.

But before I was an activist deciding to become a therapist, I was a counselor, a social worker. I worked at the rape crisis center and the trauma was fresh and never-ending and I thought: how can anyone heal their trauma when these systems keep re-traumatizing people? We have to organize; we have to cut out the rot at the root. So I quit being a counselor to become an activist. And so on, ad infinitum: I have been toggling between the self and the other, the collective and the individual, the macrocosm and the microcosm, my whole thinking life.

So I go to work every day and I see my clients. I don’t talk about Palestine, I don’t wear my keffiyeh, I don’t post my signs. I do my notes, I support my staff, I work through lunch, I answer my emails. Then I leave, I grab a bike and meet up with a group of students from the community college marching south down Broad Street, chanting “Free Free Palestine!” for a half an hour, and then I hop on the subway, home in time for dinner. I leave work and meet my husband on the Temple campus, where we weep and sob while listening to an imam, a priest, a rabbi, a hundred students holding candles as the light thins and the chill settles around us, cross-legged in the grass. I leave work and go lie down, a symbolic death, under the blue sky and coral pink clouds and setting sun at City Hall, silent while drones and helicopters buzz overhead, under a banner that says “HEALTHCARE WORKERS FOR PALESTINE,” with hundreds of other therapists, midwives, doctors, pediatricians, all desperate to stop the bloodshed, maybe risking our jobs to do so. I go home and I read about Palestine, I cry about Palestine, I dream about Palestine, I talk and I post and I strategize about Palestine. I wake up the next day and go to work, with my coffee and my mason jar of oatmeal. I think of this poem:

In order for me to write poetry that isn’t political

I must listen to the birds

& in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent

-Marwan Makhoul

Because, I don’t know about you, but personally I cannot enjoy reading Patti Smith talking about chopping sweet potatoes while newly orphaned children wander the streets of Gaza City, blinking, covered in dust, in a hellscape that blooms anew every day from the taxes I pay from my work as a therapist. I cannot care about Taylor Swift or the Great British Baking Show or even Beyoncé while my government proudly stands with the engineers and executioners of this extermination of human life: of children, men, women, families, communities, cultures, hospitals, farms, olive groves, fruit trees, vineyards, water tanks, solar arrays, schools, mosques, churches, synagogues, hearts, minds, dreams, spirits, worlds, universes. I cannot think about the Sixers or the Eagles or Princess Di or Barbra Streisand’s new memoir. I cannot.

On Election Day last week, as I walked out of the voting booth, I said, loudly, “I’d vote for a ceasefire in Palestine today if I could!” and the poll workers all raised their fists. Power to the people.

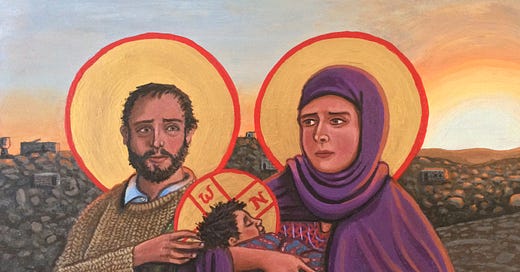

I have watched in awe and admiration as my Jewish siblings take great risks to walk the path of their ancestors in calling for ceasefire, as my Muslim siblings share culture, food, prayer, and hope under extreme duress, as my witches do the sacred work of ritual tending and healing, of making a way out of no way; as Christians of conscience see Christ in every child, every elder, every mother and father whose whole lives and families have been laid to waste, besieged and bereft.

It’s the Christians that give me the most pause because, as someone raised in the church, as someone who speaks her language, it is not lost on me that Jesus, himself, was a Palestinian refugee. And it’s also not lost on me that it’s the most fervent and rabidly self-proclaimed Christians—the evangelical, Trump-loving, gun-worshipping, Q-anon fever dream anti-vaccine Christians, the ones who have been praying for this colonization and war to hasten their prophecy of hell on earth—that cannot stop themselves from crucifying Christ every single chance they get, because every Palestinian man, woman, and child that cries out in anguish, that perishes in this hellfire—Ah, buddy, that’s Christ Himself.2

The problem—this loss of our collective humanity—is a spiritual problem, and so too, is the promise in our movement a spiritual promise: spiritual not as in religious but as in finding meaning and purpose in being a part of something larger than one’s self; spiritual as in literally, etymologically, being a part of the breath of life.

I had COVID over Halloween and las Dias de los Muertos, and I couldn’t build an altar to the beloved dead, the ones we lost this year and years past, the way Glo taught me. But at the march to free Palestine in DC last week, there they all were: I felt Sinéad there with us, her beautiful warrior spirit (my god, she loved to see it), I felt my old friend Matt there, rolling with the crowd in his scuffed-up wheelchair playing his penny-whistle with a wry smile—a martyr if ever there was one. I felt Glo there, her spiritual presence like a great winged bird encompassing the whole sky; I felt Nicky, who we lost last year at 17—I saw his face in the faces of the teenagers standing on top of garbage trucks stopped in the middle of the street, waving flags, defiant and proud.

We don’t have to choose; there is no difference: our lives and minds expand and contract, ebb and flow. And so it is that I have found myself, at the crossroads of both and and. I don’t have to choose between being a therapist and an activist. I am an autonomous individual, and I am inexorable from the collective. I cannot separate my work with individuals from my work with systems and communities, any more than I can separate my inhale from my exhale.

Every self is the other, and every home is the whole wide world.

A Card.

The five of hearts (cups) is called The Lord of Loss in Pleasure or, more plainly, Disappointment. It points to grief and loss, yes, but also to the disillusionment of looking back and taking stock and and having to let go of how you thought things would be or could be or should have been; letting go of the path not taken, all the worlds unknown because of the path you chose, or the path that was chosen for you.

May we make peace with our disappointment, may we give up hope of that which can never be or come to pass. May we become disillusioned—relinquishing our illusions in order to engage with life on life’s terms; engaging with the truth, however heartbreaking. May we look back to the past to gather what parts of us are intact and worth salvaging, and then move forward into the future with love and clarity and bravery and strength and humanity. So mote it be.

Home + The World is a weekly newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. All content is free; the paid subscriber option is a tip jar. If you wish to support my writing with a one-time donation, you may do so on Venmo @Jodi-Rhoden. Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.

⚔️❤️ Jodi

I tried to quit; I sometimes still find myself doing cancel-culture-y things, specifically on the internet, in the name of safety or “deplatforming abusers” and it can sometimes feel impossible to discern if I’m protecting my people or just punishing a human who made a mistake or maybe didn’t, because social media is a hall of mirrors too. I try to be gentle with myself, and forgive myself, and forgive others for the same missteps. Progress, not perfection. Perfect is the enemy of good.

from Franny and Zooey by J. D. Salinger

A powerfully written piece. A meditation on healing- for everything! Heart opening and exhausting and so diametrically opposed to “othering”. It left me bringing forth a question that remains, always, in my heart. How is that compassion resonates in some and not others? What is the way toward heart opening and reconciliation? It is as simple as living honestly and with commitment to others that this anti-virus will diminish?