Greetings from the mulberry tree dropping its leaves in the wind, greetings from the morning moon, greetings from the smell of shrimp and grits wafting through the screen doors and onto the sidewalk, where the maypops ripen and rot. It’s almost mid-October, but it’s still early autumn here in the Delaware River Valley, where life is so full and I want to do everything: on my one free day this week I simultaneously want to walk in the woods with a friend all day and read in bed all day and fix the drywall and make cookies and soup and kraut all day and also wander the aisles at Target all day, contemplating olive wood salad bowls and yoga mats and lip glosses and picture frames. After years of feeling like an empty vessel, a husk, a shell, a void—all manner of green things are taking root and tendril in me, birds and seashells in my hair, a pair of fawns nestling in my ribcage, fingers and toes dripping with honeycomb, everything growing, riotous and mythical and bright.

Like

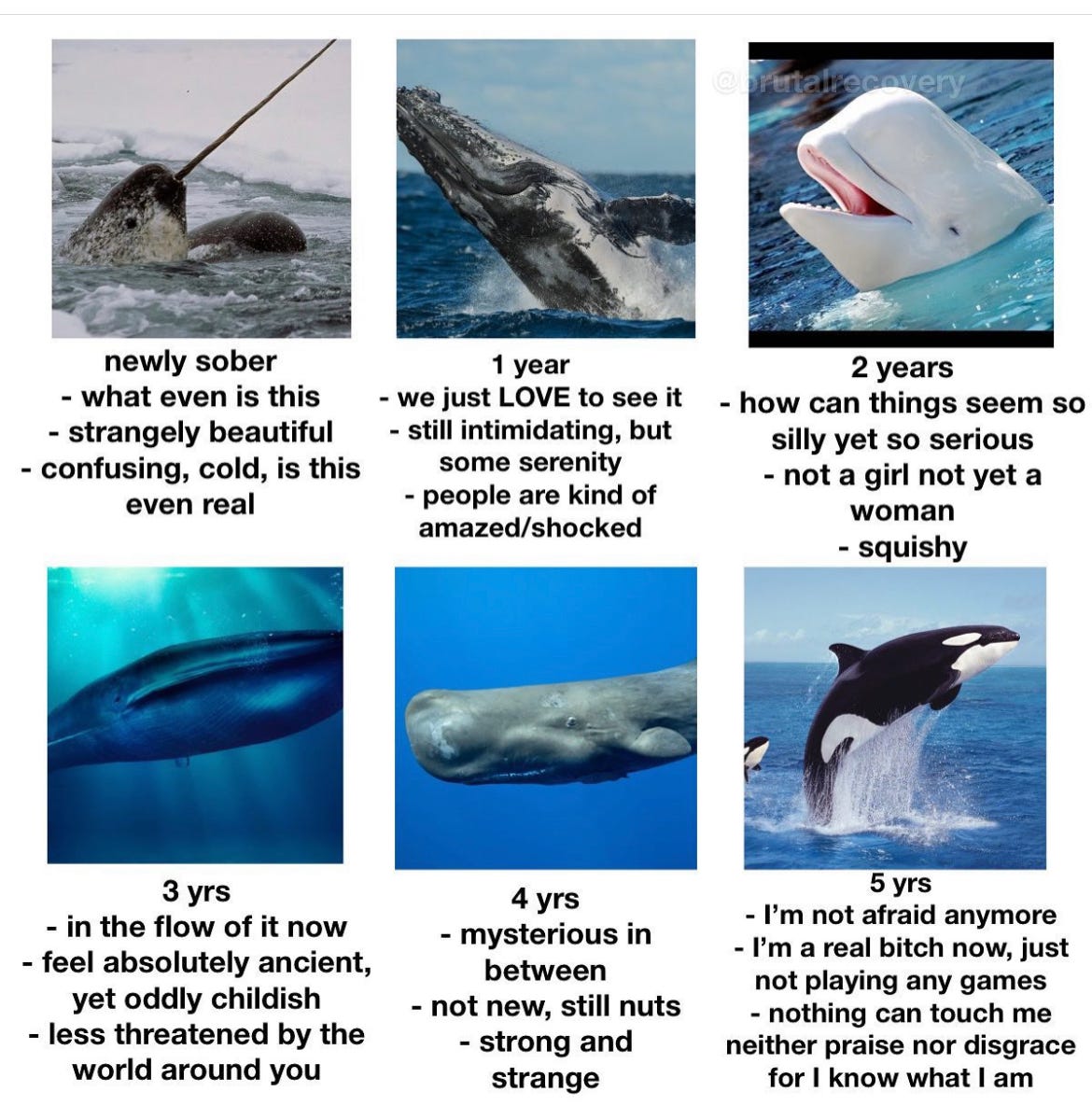

, I feel “full with the harvest, a harvest freak, proudly so,” though I don’t claim to be living close to the land as she is, “canning late into the night, my trailer smelling like slow cooked bones or pear butter,” but full with the harvest, oh my, oh yes.Last week I… acknowledged? observed? recognized?… four years free from alcohol. “Celebrated” isn’t quite the right word, because it doesn’t seem like a celebration so much as a solemn remembrance. I didn’t go out to dinner and raise a glass of sparkling cider, I just prayed and remembered and cried with relief.

Four years feels exactly like this: a mysterious in-between, strong and strange, a toothed whale, a leviathan, swimming deep.

Sometimes I diminish my own recovery because I work with women every day whose opioid use has more visibly catastrophic consequences than my alcohol use: women who have lost custody of their children, lost their housing, lost their jobs, lost limbs, all manner of illnesses from precarious living, from medical care delayed and denied.

But then I remember that alcohol kills just as many people annually as opioids,1 that alcohol-related deaths among women, especially young women, increased 14% per year from 2018-2020 and are climbing, that I have survived many of my own extremely risky behaviors, that I have put my own child in danger due to my addiction. I remember the itch of my skin in the night.

I remember that recovery is recovery is recovery.

I remember that I’m not better or worse or safer or riskier or cleaner or dirtier and neither are you.

I remember that we are not separate, not different in any meaningful way.

I remember that my recovery didn’t begin that night four years ago (how could it have only been four years ago?) that I had my last sleepy, anticlimactic vodka soda on a couch in Chicago. My recovery didn’t begin the previous summer, when I managed to string together five sober weeks, white-knuckling. My recovery began decades ago, every time I prayed in my journal to quit, every time I gave myself a molecule of compassion, every time I remembered to live in what Heidegger2 called the “state of mindfulness of being,” that is, refusing to live in humanity’s default “state of forgetfulness of being,” even if only for a moment at a time, remembering to be aware of my own finite existence, of the fact of being, remembering.

The women I work with are like all women in that they are taught to hate themselves: they hate their bodies, they hate being in pictures, they hate their chins and their ankles and their necks and their hair and their lips and their stomachs; they especially hate their stomachs, to a number, the soft and stretched places where they grew life, against all the odds. They’ll remember to eat for the baby, but starve themselves after giving birth, they’ll cook for their partner, but not for themselves. Men on the street ask them when the baby is due when they are not pregnant and they dissolve into the abject shame of having a body, of being a body, something that has happened to me many times since the one time I actually was pregnant, being asked by a man to explain my stomach, which serves to remind me that my body is not for me to experience but for men to perceive, to evaluate and categorize, which is a way of forgetting, a clever trick to keep us from remembering the fact of our being.

The women I work with are like all women in that they survive being molested and then get blamed for it, they survive being raped and then get blamed for it, they survive being abandoned by the people that were supposed to protect them, then endure the humiliations those same people cast upon them because of their “choice to do drugs” their “lifestyle,” to a number. They survive lies, secrets, getting punched in the face in their sleep. They take it all in, and they believe it when they are told that they don’t deserve better. They are programmed to disappear, dutifully, to destroy the scene of the crime, to forget, to forget, to forget.

I’ve been imagining my own death lately.

Not in a way that wishes to hasten it, but in a practice of acceptance way, in a shavasana way, in the way described by

in her beautiful essay on death anxiety “Notes on Rot”:The rain came on Saturday night. Sunday morning the sky was dark gray, the dogwood leaves dripping. I imagined my own body, dead on the ground, rain softening me up like a zucchini on the vine. There’s nothing special about death, about rotting. It happens to the best of us. That image didn’t stop me from scurrying around, packing it in for winter. I did can the tomatoes, and the apple butter, and I did my best to protect the remaining starts. I didn’t get to the basil yet.

Cultivating a practice of remembering that death is inevitable, that it will, definitely, happen to you and everyone you know, is kind of a reverse-engineering way to remember the fact of one’s being and existence, a way to wake up from the forgetfulness of being.

Recently I attended a pottery night event hosted by a learning collaborative of professionals who work in the field of perinatal opioid use disorder:3 OBGYNs, pharmacists, therapists, hospital and non-profit administrators. I had two profound takeaways from this.

Number one: I’m a pottery bitch now.

And number two: everything about the way this system is set up serves to blame and punish women for the ways they have been harmed.

For example: after a pregnant person on methadone gives birth (being on methadone while pregnant being the right thing to do, the gold standard of treatment, the thing they are told to do), often their dose is suddenly too high and they can be over-sedated when they medicate until they can, in consultation with their provider, get to a newly stable dose. In the meantime though, this over-sedation can, of course, pose a risk for the well-being of the baby, in all the different ways that you can imagine, which increases the likelihood of that child being harmed, and that mom getting reported to DHS, which all of us are required to do if a parent is not able to adequately supervise her baby.

But what if, instead, Medicaid or DHS funded a doula that could be with her for the 4 hours after medicating each day while she finds her stable dose? Can you imagine a more humane response? Can you imagine all the collateral benefits of this arrangement for the parent, the babe, the community? What is the cost to us, to our societies and families and individuals when our children are taken from us as punishment for our societies and families failing to show up for us?

We are living it.

Last week on the way home from work, instead of taking the train, I walked for hours. I walked through beautiful Chinatown during preparations for the Mid-Autumn Festival just as the piano intro of “Dancing in the Moonlight” twinkled into my AirPods, and I strode past throngs of families and buckets of live crabs and tidy stacks of steaming translucent white dumplings and piles of golden mooncakes wrapped in cellophane and racks of jade and jasmine plants for sale on the sidewalk and giant fish breathing, bug-eyed, in shallow orange crates and I got that feeling again: when every face I see I think is either someone famous or someone I went to kindergarten with, a feeling of profound dissolution of other-ness, when I remember to remember to remember.

People seem extra conscientious on the subway these days. I’ve been riding the trains since I moved here three years ago, in the first bleak pandemic winter when there was almost no one in the tunnels but the unhoused, and now the city is awake and alive and every car is packed with school kids, commuters, elders, parents, and yes, the unhoused, the people with no where else to go. And amid the crush and thrum of humanity, lately it seems to me (maybe it’s just me) but it seems to me like everyone is taking a little extra care—a stepped-on toe or a lurch from a sudden stop yields hands held up in peace, eye contact, “you ok?” “my bad.” We are alive, for now, ripe for the harvest, and we are the same, bound together, each to each.

I believe that we are trying to remember.

The World

Have y’all noticed all these articles recently about how the solution to the world’s problems lies in getting all these sassy single ladies to settle down with a man? Me too. And thankfully, I don’t have to tell you how I feel about it because Rebecca Traister already did:

At this point, I’m getting annoyed at how good

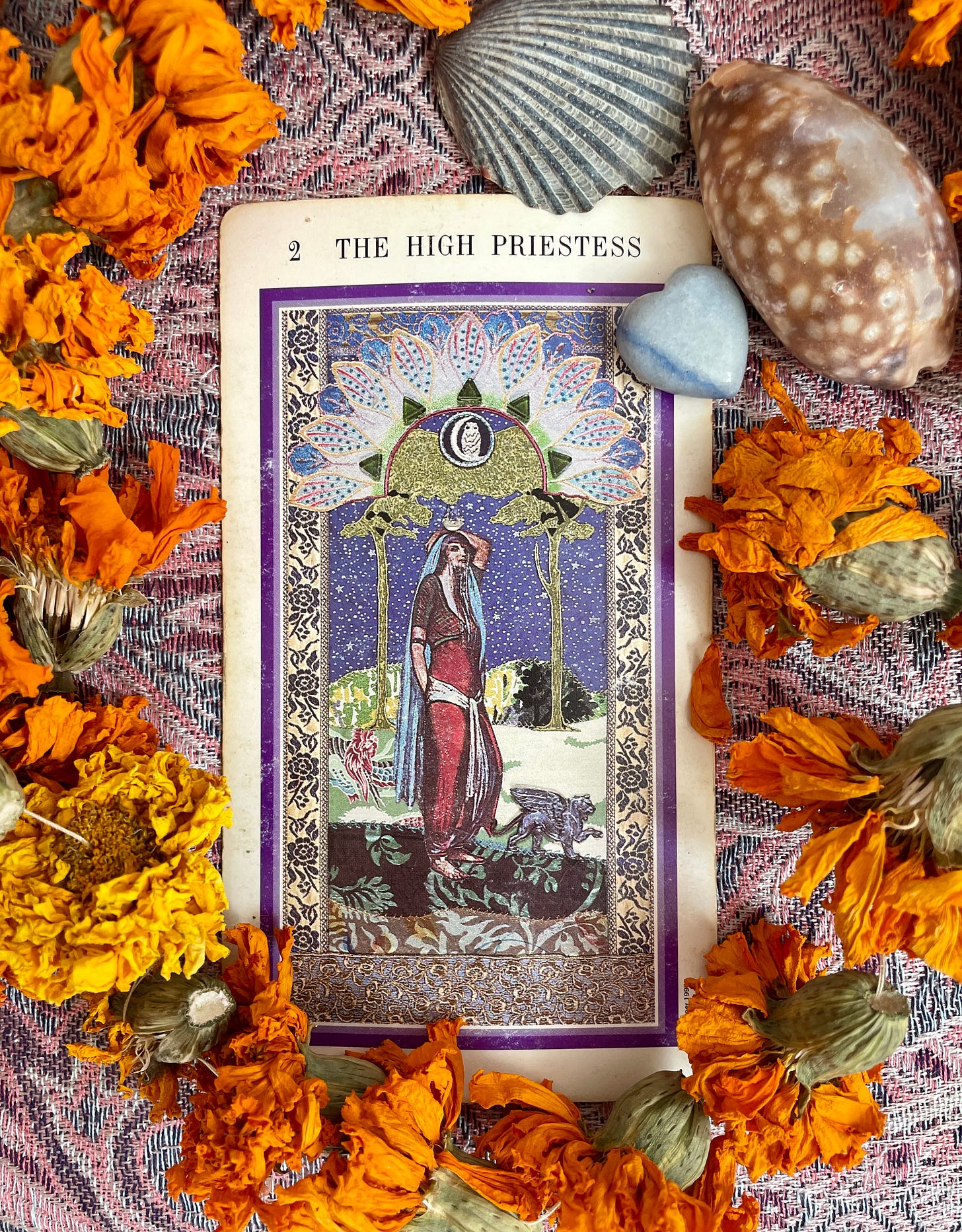

is, but I can’t in good conscience deprive you of this essay:The High Priestess

In Tarot, it is important to note the progression of the cards as well as the meaning of each image, particularly in the Major Arcana, which represents the journey of the soul (the fool) through life. Here we see the wisdom keeper, whom the fool encounters only after they encounter the Magician, who shows them their own resourcefulness and skill. Now, the fool must leave behind skills and resources and rely upon their own inner wisdom; they have to go dark, go deep, go quiet. Only then can they access the sacred, obscure knowledge that the priestess keeps. In this season of death and dying, of endarkening and sleepy cozy rest, in this season of harvest and rot, may you find the wisdom you seek, inside your own soul, there all along.

Home + The World is a weekly newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. All content is free; the paid subscriber option is a tip jar. Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.

⚔️❤️ Jodi

More, actually, but it’s not a competition

As interpreted by Irving Yalom in his book Existential Psychotherapy

“Perinatal” refers to the period of time from when someone becomes pregnant up to a year after giving birth. So people who work in the field of “perinatal opioid use disorder” are people who work with pregnant people who use opioids/are in treatment for opioid use disorder and their babies, who are sometimes born with NAS (Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, the less-stigmatizing, more person-centered way of saying “babies born addicted to drugs”). OUD in pregnancy is usually treated with methadone, a MOUD (Medication for Opioid Use Disorder, sometimes/formerly known as MAT, Medication Assisted Treatment).

Recovery is hard. Over 3 decades have taught me many things. one thing that has come to me is that men and women have a very different experience in recovery. (Duh, right?). Shame is heaped on women, by society, family, friends, ...... everyone. So, what I have to do is ignore other’s opinions. Period. I need to value myself and my opinion and let others have their own. Detach for the sake of self preservation.

So moved by this memoir. It’s is packed with wisdom and reality. Reading this once may not be enough; although it is brief it is a tomb. So much to reflect on and a reminder that being mindful, staying in each moment is the richest most meaningful way to live, especially when we realize how fleeting life is…