I’ve always been fascinated by cults.

To be honest, I’m a prime candidate for cult membership: perpetually spiritually seeking, hardworking, and desperate for approval, it’s a wonder I didn’t get swept away by the first Hare Krishna devotee or Zendik Farm magazine street vendor I came across as a 14-year-old punk wandering around in Little Five Points (that hotbed of 90’s Atlanta counterculture, where I bought my first clove cigarettes, Manic Panic hair dye, and black-and-white-striped knee-high stockings). Maybe I have my contrarian nature to thank for that, or my tried-and-true impulse to bolt as soon as a thing starts to feel boring or constricted.

Resistant to indoctrination though I might have been, I’ve been a part of or adjacent to many spiritual, political, and communal living experiments in my life: the Catholic Worker movement, Dzogchen Buddhism, Radical Faeries, various autonomous anarchist collectives, Asheville in general. But I think it all started with summer camp.

Camp Toccoa, in the hills of North Georgia, was my first commune. I first attended at age 7, and became an immediate evangelist: here was a ready-made world, complete with a secret language of songs, insignia, and jargon, an all-encompassing system of shared work, art, craft, play, and meals, an order and an ethos under the stars, where everybody could shine.

And HORSES!

Camp Toccoa was my life throughout my childhood, the perfect world I dreamed of during the mundane year full of mores and systems (family, church, school) that were incomprehensible to my mind and offensive to my sensibilities. Why am I taking a standardized test when I should be building a fire in the rain? Why do I need to know the difference between a salad fork and an dinner fork and a fish fork for god’s sake when I should be foraging sumac berries and digging sassafras roots for tea?

But every utopia has its dark side, its fall from grace, and mine came in the form of getting fired from Camp Toccoa after my first perfect summer as a counselor, for smoking weed at the winter staff reunion campout on Flat Rock, along with half the staff: my community, my cohort, my pen pals, my best friends, my first kiss. And just like that, we scattered to the winds; and we had to find other places to try to belong.

Since then I have tried to permanently insert myself into many different forms of communitarianism, but they all ended, either in an abuse of power (most frequently seen in the most fervently egalitarian spaces), a violation of boundaries, or, as was most often the case, in a general depletion and exhaustion of everybody’s earnest resources, time, and energy. Once we had the baby, we closed ranks into a nuclear family: a struggling, contentious commune of three.

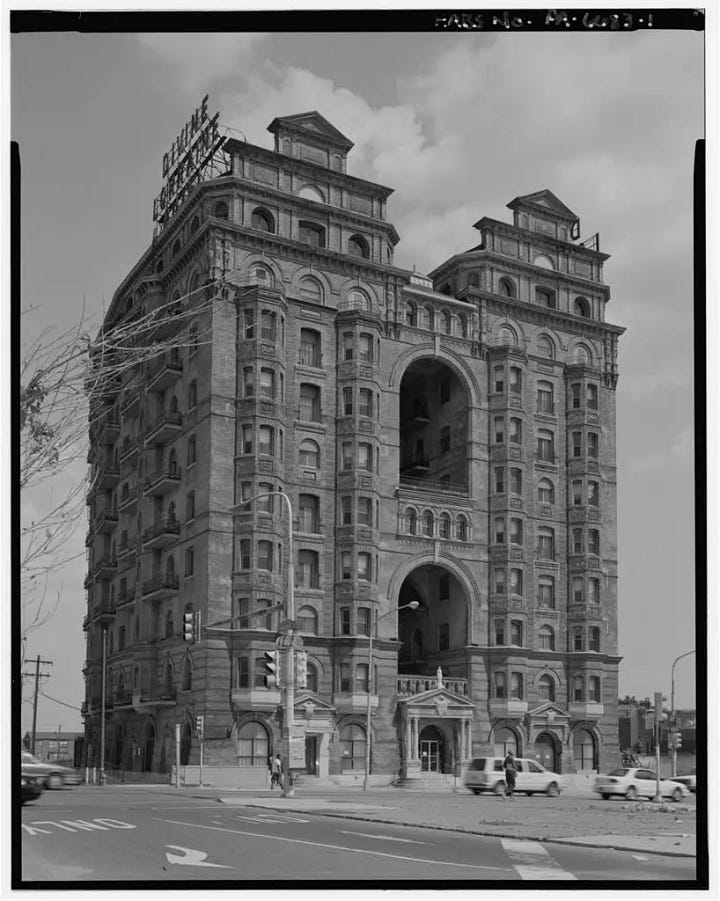

But I’ve always yearned for community, an extended kinship of hardworking people rallying around a noble organizing principle, sharing the load, us against the world. Which is, perhaps, why I’m so fascinated by Philadelphia’s Divine Lorraine Hotel, and its history as the headquarters of what was once the largest and most influential religious and civil rights movement (and, yes, cult) of it’s time: Reverend Major Jealous Divine’s International Peace Mission.

According to Wikipedia, “Father Divine was worshipped by his followers as a God. Father Divine preached against sexism and racism. He was most renowned during and following the Great Depression in the 1930s. The International Peace Mission movement emphasized its opposition to violence and war. Also the movement has a very strong focus on spiritual development through meditation and prayer.”

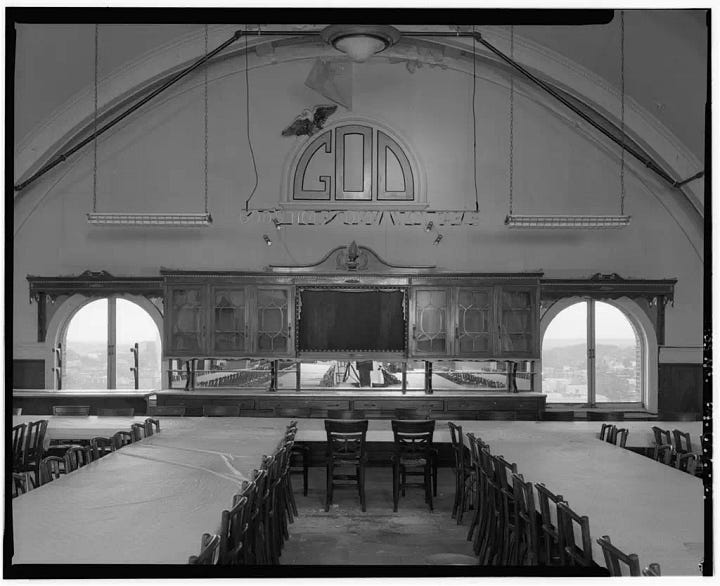

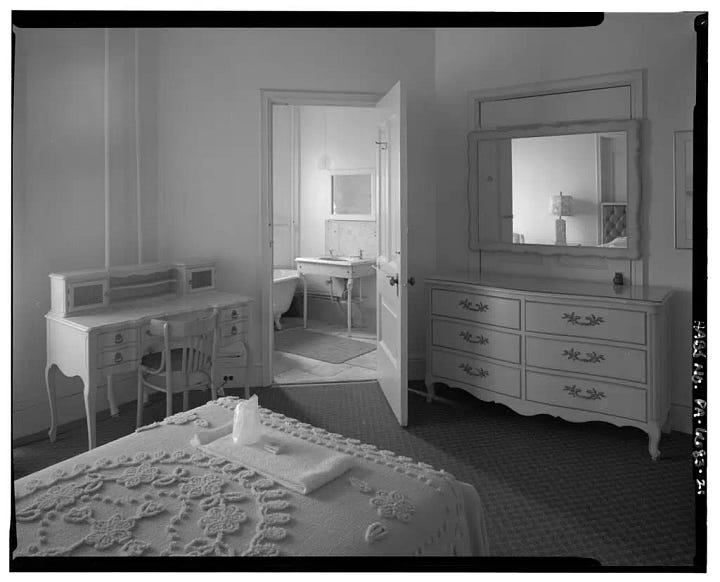

Originally built as the luxury Lorraine Apartments in 1894, Father Divine purchased the Lorraine Hotel in 1948 and gave it the name Divine Lorraine Hotel, creating the first racially integrated hotel in the United States. “The 10th-floor auditorium was converted to a place of worship. The movement also opened the kitchen on the first floor as a public dining room where persons from the community were able to purchase and eat low-cost meals for 25 cents.”

As this piece from Eater states: “historians have argued that his vocal opposition to segregation made him a link between Marcus Garvey and Martin Luther King Jr. Father Divine was equal parts holy man, charlatan, civil rights leader, and wildly successful restaurateur. The key to his movement’s influence and longevity could be found in the bit that started it all — food.”

Were there sex scandals? Definitely. Was there misappropriation of funds? Most certainly. Would the International Peace Mission fit the definition of a “high-control group?” most likely. But Father Divine fed people when no one else would.

After Father Divine’s death in 1965, membership in the International Peace Mission declined, and, one by one, his widow, Mother Divine (who was his 21-year-old secretary when he married her at age 70), sold off the church’s holdings, including the hotel. A small community of devotees still lives at Woodmont, a chateauesque mansion in Gladwyne, Pennsylvania. The hotel fell into disrepair from the 1980’s until 2015, when it underwent a $44 million renovation.1

To celebrate our 21st wedding anniversary last month, Duncan and I went out to dinner at the elegant Italian restaurant in the first floor of the newly renovated Divine Lorraine Hotel. We dined on octopus, wild boar, lamb, swordfish; the server placed a small velvet stool next to my chair, on which to set my handbag. Everything was impeccable—except for one thing. The dining room—forty or more tables under glimmering mirrors and grand, arched windows lined in luxe drapery—was completely empty. We thought maybe, since our reservations were somewhat early, that the room would fill out. Almost three hours later, after lingering over our figs and arugula, our coffee and bottled sparkling mineral water and rich handmade French vanilla ice cream doused in sea salt and olive oil, there had been exactly one other table seated and one small party at the bar, and we realized that no one else was coming.

“It’s kind of unnerving to be the only ones here,” I whispered to Duncan.

“Well, we’re not really alone,” he responded, upbeat, “just imagine every table full of ghosts.”

I looked around, and indeed, there they were, clamoring, the spirits, the legacies, the imperfect lives and loves that sang and felt and lived and died and were fed, in body and spirit, in these halls.

Post Script: There are so many more things I wanted to say about the Divine Lorraine, and cults, and conspirituality, and narcissistic abuse and magical thinking that I could not fit into today’s one-day-a-week writing practice. I’ve thought about changing things, posting less often and going more in-depth, but there is something beautiful about the ticking clock on these Sundays outside of time, this experiment, this weekly offering to the gods of shitty first drafts, the gods of butt-in-chair, the gods of sitting-down-at-the-typewriter-and-bleeding. So far we have completed three seasons together, readers; thirty essays—a winter, a spring, and a summer; and now we embark on a fall to complete one full circle of a year. I don’t know where this is going, but I am so happy that you’re here with me.

Home.

I haven’t shared a houseplant update in a while, because, to be honest, I felt so disheartened by my absolutely intractable fungus gnat problem, and gave up. Fortunately, I think that they just needed time to dry out and acclimate to the new soil, and while I can’t say that the fungus gnat population is zero, I can say that I rarely see them anymore, and, aside from a few anemic, yellowing leaves on my new monstera (I just fertilized yesterday, will keep you posted), and the jade that dropped half her thick, green coins from some kind of mold or fungus (which I treated with neem oil and now is covered in new growth!)—I can happily say the plants are thriving. I made y’all a lil’ video montage of my plants this morning and I’m so glad I did; it has made me appreciate them all the more.

Temperance.

This card seems so apropos of the season of balance: Temperance represents the artful blending of elements in perfect proportion. Temperance embodies clarity, peace, harmony, tranquility, abstinence, the tempering and quieting of extremes. This equinox season, may you find yourself centered, may you find yourself at the center of yourself. 🩵

Home + The World explores the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. All content is free; the paid subscriber option is a tip jar. Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.

⚔️❤️ Jodi

More about The Divine Lorraine and the International Peace Mission:

“Religious Cult, Force for Civil Rights, or Both?” by Adam Morris in LitHub

God, Harlem, USA, by Jill Watts. The name of her book derived from the fact that before Father Divine moved to Harlem, his followers sent letters to him simply addressed to “God, Harlem, USA.”

Father Divine: The Greatest Civil Rights Leader You Never Heard Of! by Lori Tharps

FATHER DIVINE, SPIRITUAL CHARISMATIC. Acme Newspictures, Inc. An archive of press photos relating to the charismatic and controversial spiritual leader Father Divine.