Pleasure is not one of the spoils of capitalism. It is what our bodies, our human systems, are structured for; it is the aliveness and awakening, the gratitude and humility, the joy and celebration of being miraculous. -adrienne maree brown

Content warning: this essay discusses mental illness, sexual assault and childhood sexual abuse. If you or a loved one is in need of mental health crisis support, call or text 988 for the National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

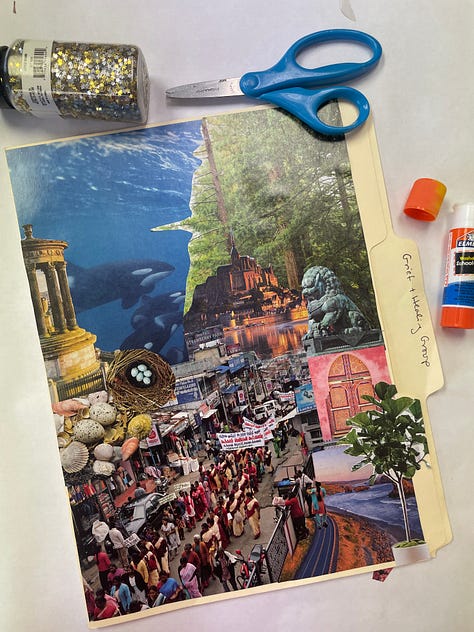

This week, Jupiter arrived in Taurus and the New Moon followed suit, and, true to Taurean signature, I found myself immersed in the mundane pleasures and earthly delights of beauty, food, and the body: making collage during grief group at work, getting a haircut that felt like a party, slowmaxxing the grocery store; romance and houseplant care and seedling shopping and a new sparkly jumpsuit thrift store score; cooking a rich pasta Bolognese with Jasper last night blasting The Cure and Pavement and The Smiths. An embarrassment of riches.

If astrology is true in the way that poetry is true,1 then the movement of the stars and the planets and the constellations’ resonance with the life cycles on earth simply remind us to pay attention to what is already here. The moon is in Taurus? Why not tune in to the earth and take pleasure in having a body? Why not, as the poet Wendell Berry reminds us, “come in to the peace of wild things” when “despair for the world grows in me?” And, oh, how despair for the world does grow in me.2

I’ve been thinking a lot about Bruce K. Alexander’s dislocation theory of addiction since reading about it in several pieces by

(but most recently in this roundup from April). Alexander is one of the psychologists who conducted the Rat Park studies in the 1970’s, which, while imperfect, helped to further the understanding that addiction is not simply an individual brain aberration but a social problem. Alexander’s subsequent and current work furthers this understanding, ultimately asserting that “addiction arises in fragmented societies because people use it as a way of adapting to extreme social dislocation. As a form of adaptation, addiction is neither a disease that can be cured nor a moral error that can be corrected by punishment and education.”Addiction is our brains simply doing their jobs so exquisitely and so beautifully: when the substrate of purpose and belonging from which human life flourishes becomes dislocated, fragmented, toxic, our brains stand in the breach: compelling us to do whatever has to be done to keep the meaning machine humming, to numb the pain.

When my panic disorder was at its height in my twenties, I didn’t experience pleasure so much as an occasional temporary reprieve. I didn’t watch TV or movies for about a decade because I couldn’t sit still that long for fear that I was being lazy, wasting time, worthless. And besides, there was no turning my brain off: any scene of violence or harm could trigger a fresh panic attack or weeks of intrusive thoughts; I felt breathless and trapped in movie theaters.

Of course, the drinking helped. When I drank I could turn the volume down on my anxiety long enough to find myself again: the me that was fun, funny, alive, fearless. And the brutal hangovers- sweaty, shaky, pukey, anxious- they were comforting in that they aligned with what I understood to be the truth of things: that there was something very wrong with me.

Resting never occurred to me. Care never occurred to me. I had an embarrassing problem, a failure of character really, and it was my fault and therefore my job to solve it, and I tried to inconvenience others with it as little as possible in the meantime. In the meantime, I tried to be useful, at least.

The year I returned from New Mexico, Sam and I (and a rotating cast of beloveds and strangers) moved into a hilltop bungalow on Carr Street in Athens, Georgia, surrounded by a wide expanse of backyard sloping down towards the Oconee River. I took an intro to Anthropology course that winter, and my professor, Dr. Virginia Nazarea, was just starting the Southern Seed Legacy Project,3 an endeavor to cultivate and preserve not just the heirloom seeds that were specific to our region, but the oral histories and stories that they contained. Participants would be given seeds for free, on condition that they participate in research interviews and save some seed: giving a third of the seed yield back to the project, keeping a third to plant the next year, and giving a third away. Though I had never once in any way gardened (my parents, who both grew up farming, saw no romance in green and growing things), I signed up. I collected my manila envelopes of seeds along with their descriptions written in pencil on the back, and then I immersed myself in books and planning, and Sam and I dug beds by hand from the crabgrass and red clay. We amended the soil and planted moon and stars watermelon, and mounds of three sisters: corn, beans, and squash planted together, an indigenous method that facilitates the symbiotic relationship between the three plants.

Both my grandfathers, in addition to being farmers, were county soil agents, mid-century preachers of the gospel of monocropping, petroleum-based fertilizers, and pesticides, so when my Grandaddy came the 20 minutes down the road from Monroe to visit he eyed my unruly plot with suspicion: “I know what you’re trying to do,” he said with gruff disdain, “you’re trying to be one of those OR-ganic gardeners.”

“Yeah! What do you think?” I replied, trying to be upbeat.

“Won’t work.” he sniffed, and walked away.

But it did work. It worked beautifully. It was the most beautiful garden I’ve ever grown, still to this day. The stalks of corn and the vines of beans and the carpet of squash leaves and watermelon grew with such insistent lushness that one could step into the garden as into a jungle- fully immersed in cool green, breathing, living creatures, sprung up from nothing, from nowhere, magic. I saved copious seeds and passed them along. I was bewildered, enchanted, bewitched. I felt the old gods speaking to me, encouraging me: you can do this! Don’t stop!

The next year, I began my year-long unpaid internship for my social work bachelors degree. I found a field placement at the Sexual Assault Center of Northeast Georgia as a counselor and case manager with survivors of sexual assault and abuse. Since I had experience working with kids at summer camps, and since it was the hardest thing to do and therefore no one else wanted to do it, and since I didn’t question that it was obviously my job to do the hardest thing to do that others didn’t want to do, I volunteered to specialize in working with the teen and adolescent survivors on our caseload, which encompassed a dozen counties of the Piedmont and Southern Appalachia.

The survivors I worked with were the ones who were lucky enough to have somebody believe them, to have an active case in the court system, to have an advocate in the schools, to have a mother (usually a mother) who was competent enough to believe them AND help them report the perpetrator- most often the mom’s husband, boyfriend, father, brother, or son- a mother who was willing to have her life turned utterly upside down to protect and believe her child over another family member or a raft of family members, usually at great social and economic cost. For most people, the cost of believing is just too high.

Unsurprisingly, my mental health worsened: the unvarnished stories of my clients’ trauma triggered seismic, pulsating anxiety and grisly intrusive thoughts. I now understand what I did not then: my anxiety was my nervous system’s brilliant, heroic effort to protect me from what it saw to be the greatest threat to me: seeing and acknowledging my own trauma. The closer I got to that truth at the core of my psyche, the louder and more chaotic my internal landscape became. Not knowing what else to do, I simply white-knuckled it: I gritted my teeth and pushed through.

I drove around the foothills and picked up my kids, the girls I worked with, from their schools and their homes, and took them to the Flying J truck stop diner for a meal, where we would talk about it, but just as likely not: sometimes it was just boys and classes and friends they wanted to talk about. I realized that, for where the kids were developmentally, what they needed was not more talking but more connection: positive peer relationships that would help them feel seen, heard, validated.

That summer, buoyed by the abundance of my three sisters garden, I started a summer garden club with my teens. We met weekly to plant and tend a community garden on some land outside the Council on Aging, and talk about self-care, and healing, and growth, the lessons I most needed to learn. Once again, the garden, the earth herself responded, and reciprocated my care back to me, manifold.

At the end of that year, I graduated college, and I left the job, and Duncan and I left Georgia, left the house on Carr street and the gardens, and began a new chapter in the new millennium in Boston. I decided that I didn’t want to work in trauma for a while, that I needed to build upon what was life-giving, that the old gods were calling me back to the garden, and I worked for the next many years in farms and food, green and growing,4 healing.

And now, the thing has come full circle, as things tend to do. I’m back in the belly of the beast, deeply engaging in trauma and healing work as a therapist with women with opioid use disorder, which is to say the exact same population as the girls I worked with in Georgia because, as my grad school professor Dottie Greene liked to say, trauma and addiction are married. This time, I’m a little more oriented, a little more resourced. I can feel my feet planted firmly in the soil. This time, for now, I’m not drinking from an empty well, I’m not wringing blood from a stone. I’m here on earth, tending. And I don’t take it for granted, the joy, the pleasure, the meals and the music, the honeysuckle and the milkweed, the movies, the marigolds, the manure, any of it. I try take it as a gift, I try to take it in, I try to taste it.

Embodying creativity, fertility, fecundity and the giving and receiving of pleasure, the Empress revels in the beauty and bounty of joy and connection. This card carries a wish of rest, nourishment, and love, and I hope you find it in the here, now, and always. In that spirit, I’ll be taking next week off for the holiday!

See you in two weeks. ❤️

Home + The World features personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.

⚔️❤️ Jodi

something I heard said on the Skyline Drive podcast

the poem we contemplated in mindfulness dialogue this week at work

I found the final report from this project!

hat tip to David and Hayley for this turn of phrase