Some of the folks we've met who ended up fighting or running to stay alive seem to me to have a brightness about them. Even in the midst of all this loss and uncertainty, the sheer fact of their aliveness has become all the more precious and astonishing.

-Rae Anderson, Western North Carolina

On September 11, 2001, Duncan and I woke up in a hotel room in North Carolina, where we were scouting jobs and houses to rent. We were planning our move to Asheville from Boston, Massachusetts—and the Catholic Worker community we called home.

Life in Boston—the cold, the expense, the distance from my family in Georgia—had become untenable. Asheville was to be our happy medium: the South but not all the way south, the South but still with four seasons, the South but an oasis, a queer misfit mecca where people like me, people who didn’t fit in in the Southern suburbs or small towns or mountain hollers from whence we came could find a place to belong (why did all the anarchists move to Asheville? goes the old joke. Because they heard there was no work 🥁).

There was no clock in the hotel room, so we turned on the TV—just in time to see the second tower collapse, to feel the first shock that would reverberate throughout the world forever. We packed up quickly and loaded up the car with gallons of water and snack food, scrambled to sign the lease on the house on Hamilton Street we had looked at the day before, and hightailed it back to Boston, past the Pentagon still smoldering, past the floodlights and steam and toxic dust of lower Manhattan, to our South End block besieged by SWAT teams for days because a woman had seen a man in a turban at the Copley Square Hotel.

We moved to Asheville a few weeks later.

On August 29th, 2005, as Hurricane Katrina made landfall, I was nine months pregnant with Jasper. I remember huddling around the computer at night with friends as a deluge of rain washed down on our little pink house on Short Street, reading in horror about the unfolding disaster in New Orleans, another node in the web of activists and train hoppers, thinking of our friends as the levees broke, the floods wreaked havoc, and the federal disaster response confounded organic relief efforts, compounded the ongoing trauma, and reinforced centuries-old hierarchies that dictated who got to evacuate and who had to fend for themselves.

I remember wishing I could go help, but I was helpless myself, navigating a life-threatening pregnancy complication without appropriate medical care. Blessedly, I found Lisa Goldstein a few days later and she safely delivered my baby the next week in the hospital at Spruce Pine, North Carolina, one of the towns which now, in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, is said to no longer exist (I still haven’t heard from Lisa, but I heard she was OK).

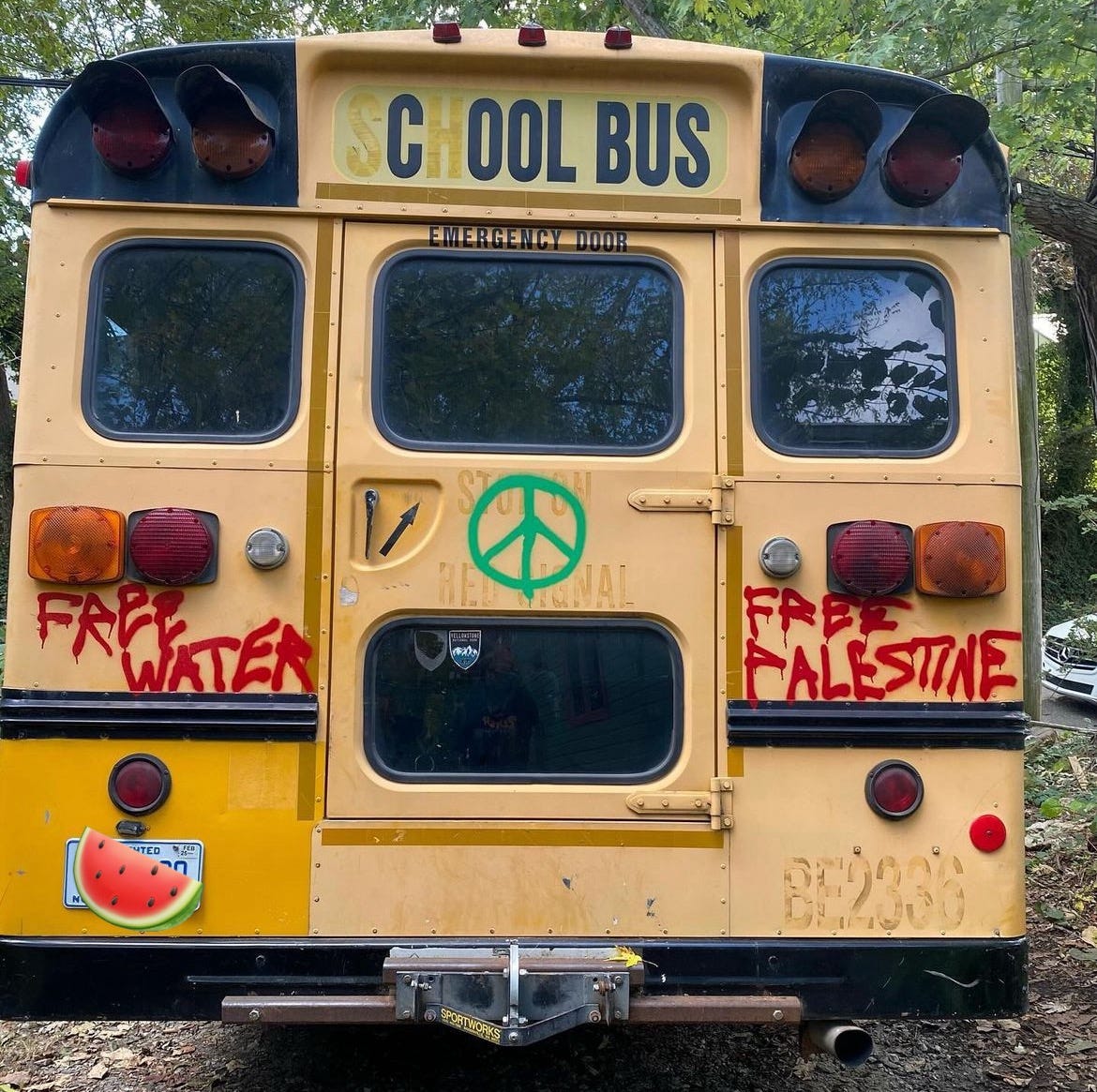

We left Asheville in 2020, in the dark of the first pandemic winter, our 19 years there bookended on one side by 9/11 and on the other by COVID-19; the in-between was bookmarked by stock market crashes, floods, wars, rumors of war. We measure our years by the catastrophes we live through, and like contractions, these catastrophes are getting closer together: the George Floyd uprisings, the escalating genocide in Palestine, and now: Hurricane Helene.

Hearing people call out to the radio asking about how yancy county is and that they're hearing nothing from yancy county while being in yancy county not being able to tell the world about the situation is something l've never thought l'd ever be in. Im so so blessed with solar power and spring water right now which is so morbid especially after how I have never had such a life threatening moment in my life. I had to grieve my death on Friday at 10:30 am and now I'm alive shocked in a place where I barely know anyone but everyone is treating me as their own.

There are farmers out here making new roads with their tractors where roads once were. There are firemen giving us lifts on the back of their 4 wheelers, people giving us rides in their truck and just allowing strangers who also need rides barefoot on the side of the road to jump in the truck, meeting neighbors to mountain gardens who have generators letting others without use them, us allowing the whole community to use our solar energy and springs, community meetings that turn into potlucks for meat that will spoil soon, I know I'm one of the lucky ones, I'm alive, l'm stuck but l'm not stuck in a home, l can walk places, there's no more flood water up here and it left pretty quickly, I survived a landslide and I will never ever ever forget the sound of the rumble before seeing a group of trees and mud slide down the mountain. The mud still stuck under my nails from having to run up quick sand mud to get to higher ground.

-Kiah Dale, Celo, North Carolina

The scale of the loss is unfathomable. Everyone I know keeps saying: there’s no way to describe what I saw. There’s no way to describe what is happening here.

What I know from watching through my phone screen is that many, many people have lost their lives. Many more people than that have lost their homes. Many more people than that have lost their livelihoods. But no one is really able to think about that yet, because most places still don’t have RUNNING WATER. Power and cell service is spotty at best.

Beautiful things are happening too, wondrous things: supplies reaching survivors by horse and foot and pack mule, everyone feeding each other. My friends are meeting up at the Register of Deeds every day to go out on flushing brigades: hundreds of people organized to bring greywater into senior highrises and public housing and flushing all the toilets. My friends are shoveling toxic mud out of each other’s record shops and art studios. My beloved

and her husband Jamie pivoted their farmstead and bakery to a mutual aid hub. The bar down the street from my old house is now a free clinic with nurses, herbalists, therapists, and acupuncturists taking shifts.What's it actually like living here right now: the best way to describe it would be like The Busy World of Richard Scarry except it's hillbillies, punks, linemen from all over the continent, doctors, hippies and nurses on horseback going into the hills. It's volunteer hikers backpacking with supplies to the places that no longer have roads. It's teachers and homeless folks working together to flush a million toilets. It's our favorite dive bar that is now a makeshift hospital. It's Fyre Fest, Burning Man, Thunderdome, Naked and Afraid and Groundhog Day all rolled into one freaky surreal fever dream. Everybody is showing up to help their neighbors and strangers.

-Mary Claire Ginn, Asheville

And, yes: many of those people shared that they did not see any state or federal assistance for the first week. My dear friend Kim Roney, an Asheville City Council member, has been sharing official updates every day, and it was not until day 5 that she was able to report that the city was distributing aid from federal and state sources.

Regardless of how this information has been twisted or leveraged, the reality on the ground for many people is that the people who rescued them, fed them, and chainsawed the trees off of their houses were their neighbors, not the government.

Regardless of how this information has been twisted or leveraged, it remains true that cops protected grocery stores instead of people trying to survive. It remains true that the Health Department has issued cease and desist orders to restaurants serving free food to survivors.

Regardless of how this information has been twisted and leveraged, it remains true that FEMA has announced it does not have enough money to make it through hurricane season (a 9 billion dollar shortfall, according to Deanne Criswell on September 26). And it remains true that on the same day, Israel announced that it had secured an 8.7 billion dollar weapons package from the United States, paid for by US taxpayers.

Regardless of how this information has been twisted and leveraged, it remains true that decades of tourism boosterism, including touting Asheville as a “climate haven” at the expense of infrastructure investments has driven increasing income inequality and made communities more vulnerable to these kinds of fossil-fuel driven climate change catastrophes.

Regardless of how this information has been twisted or leveraged, it remains the lived experience of the people at the center of the tragedy that networks of mutual aid spontaneously and organically established first aid and feeding and sanitation and supply systems.

Yesterday, I was here in town like I am now, searching for signal and hoping to feel less isolated. A man parked near a group of us. As soon as he got out of his car he was talking. He is a town commissioner for Lake Lure. He was clearly in shock. He was talking to us, rapidly, but we might as well not have been there. He was processing what he had witnessed, putting it into words and order. He described being near the lake with other town officials when a massive wall of water crashed through the business district, carrying first a shed, then what he recognized as his neighbor's house and then the entire town of Chimney Rock. He said several times that it was all over in 10 minutes. And entire community dumped into Lake Lure. I gave him a big hug. I didn't let go. He told me his grandmother died the day before. And he got back into his car and drove away.

-Margaret Curtis, Western North Carolina

Last week marked my 5 year sobriety date, which floated by with only my own most cursory acknowledgement, and of course, yesterday was October 7, one grim year of a still-expanding genocide (and on this matter: I condemn nothing but Israel. I will not participate in what Gassan Haje calls “supremacist mourning” for the victims of the Al Aqsa Flood, while hundreds of thousands of murdered Palestinians remain unnamed and unburied).

I turn on the radio, and scan between the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s percussion solo on “Take 5” and a pregnant journalist in Beirut being interviewed by NPR, responding incredulously to the host asking her casually if she wants to “drink a bottle of something to unwind.” I simply cannot process all of these things at once. There is no way to make sense of this magnitude; to orient to the multiple unfolding intersecting crises.

I’m beginning to have that cinematic feeling—that Indiana Jones feeling of trying to outrun a crumbling bridge, or tower, a collapsing cave. On my knees planting bok choy at the farm, I can only weep, everything is so poignant, so tender, so profound.

Seeing the whole city band together to take care of each other is beautiful, and in a way it should always be like this. It shouldn't take a thousand year tragedy to make neighbors knock on your door offering food and companionship. Will we learn anything from this? Will we move forward knowing that we have to watch each other's backs, or will it evaporate at the first whiff of normalcy?

After the Old Testament flood, which was supposed to cleanse the world of iniquity, the survivors rebuilt, but to what end? Forgive me for getting biblical, but it's quiet outside, except for the wailing of sirens, and all the water's turned to wine.

B. Menace, Asheville

This time last year, I wrote about foraging persimmons, but, even though I tried to collect only the jammiest ones on the ground, enough unripe fruits made it in to the mix to render the batch horribly astringent. I had to compost the whole harvest.

Yesterday, I went back to the old tree. This time, I passed over fruit with any amount of firmness in the flesh; a sign that it had not yet yielded up its bitterness. I harvested only the softest persimmons that were also still intact, jewel-like and almost translucent. I brought them home and mashed them through a sieve; I baked my first persimmon bread, warm and spiced with cardamom and nutmeg, topped with pears from a friend in North Carolina.

There is no silver lining in this story, no redemption tale, but there is hope, and maybe a lesson: may we be ever more skillful in using the resources around us to sustain ourselves and one another. May we yield up our bitterness. May we learn to read the signs. May we change and change again, and may we find our humanity and our dignity in every kind of rubble, wrack, and ruin.

And may we ride these waves of contractions, in hopes of something new being born, precious and astonishing.

Here is a short list of vetted resources for Western North Carolina (these are mostly links to instagram, which has been many people’s primary platform for mutual aid organizing and communication). Please donate directly to vetted individuals or mutual aid efforts:

Mergoat Mag, Asheville Blade and Firestorm Coop for information and updates.

Poder Emma for Spanish-language resources.

Melissa Weiss Pottery for all around badassery.

ROAR: Rural Organizing and Resilience mutual aid hub for donations and needs lists.

And here is the WNC mega-list google doc with live updates on giving and receiving help.

Home + The World is a newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake.

Home + the World observes the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, and Jodi Rhoden is a proud signatory of the Writers Against the War on Gaza statement of solidarity with the people of Palestine.

Visit Home + the World on Bookshop.org, where I’m cataloging my recommended reading in the genres of memoir, fiction, and—of course—healing, self-help, and social justice. If you purchase a book through my shop, I will receive a commission and so will an independent bookstore of your choice. Find it here!

Dear Temperance is a Tarot advice column for paid subscribers of Home + the World. Send your burning life questions with the subject line “Dear Temperance” to homeandtheworld@substack.com or through the contact form at my website jodirhoden.com. If your query is chosen for publication, you will receive a year’s paid subscription for free. Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.

⚔️❤️ Jodi

I love you, I love you, I love you! And also I am kinda bugged out at the numbers 1 and 9, and how they danced all around you in 9/11, Covid-19 and your 19 years in AVL. Wild.

I'm a new reader to your Substack and a newcomer to Asheville. It's devastating to see communities destroyed that I am only just started to get to know. Thank you for writing this, and sharing these stories. It's incredibly powerful, and so important that they get out there. What is happening here in WNC is bigger than us. Will share this essay widely!