My client tells me that she thinks she must be living in hell because—even though she works every day, stays “clean,” takes care of the baby—she can’t even afford to help the little kitten that cries and mews and rubs against her legs every morning as she walks to the subway. Maybe God is punishing me, she muses.

Another, several years sober, tells me that working incessantly and never having enough to make ends meet, caught in a neverending loop of stress and exhaustion and lack: it’s not that she and her friends want to die, but they all agree that maybe it would be a relief to just go to sleep one day and never wake up.

On my way to and from work every day, I walk past a certain street corner presided over by a neatly preserved 19th century gothic chateau, where unhoused people sometimes congregate. In the mornings, workers sweep up the detritus of the night before—contents of pilfered trash cans, a deck of cards scattered and matted to the sidewalk by the rain, a pair of soiled sweatpants.

One morning, I noticed a new addition to the collage of fresh filth lining the sidewalk: tiny pieces of pink, bloody, raw flesh, the guts of a fish—or maybe a rat—neatly arranged, mandala-style, on the billowing steam grate in the sidewalk. Now, months later, the morbid installation remains, sinewy, blackened and dried, cemented to the antique wrought iron by a cycle of steam and sun, a scene so particularly gross and visceral that it seems to be lifted straight from a Hieronymus Bosch hellscape.

A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster is the title of a 2009 book by Rebecca Solnit, exploring the “temporary utopian societies naturally arising in the midst of casualties, disorientation, homelessness, and great loss of all kinds.” Her book posits that—contrary to the premise of every zombie apocalypse movie ever—when extraordinary devastation and sudden social collapse occurs, humans do not naturally and instantaneously devolve into looting, raping, cannibalizing maniacs, but rather come together spontaneously, in altruism and solidarity, to help each other. But, as Jonathan Greenberg writes in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, “the cooperative, life-affirming social experiments Solnit finds so often in the ruins are fleeting. They disappear when established institutions of governance and patterns of social behavior eventually return.”

Established institutions of governance and patterns of social behavior—these are the conditions that keep us from running towards each other in mutual support, in connectivity, in solidarity.

One of the five disasters that Solnit studies in the book is the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, of which an 8-year-old Dorothy Day was a survivor. Day later wrote of this experience as foundationally formative to her life and ethos:

“What I remember most plainly about the earthquake was the human warmth and kindliness of everyone afterward. Mother and all our neighbors were busy from morning to night cooking hot meals. They gave away every extra garment they possessed. They stripped themselves to the bone in giving, forgetful of the morrow. While the crisis lasted, people loved each other.”

Solnit wrote: “Day remembered this all her life, and she dedicated that long life to trying to realize and stabilize that love as a practical force in meeting the needs of the poor and making a more just and generous society.”

In 1999, Duncan and I lived in a tin can trailer in a piney wood, the sole human inhabitants of a 500-acre horse farm 20 minutes outside of Athens, Georgia, where we tended the horses and the land in exchange for rent. On Sunday mornings, the local college radio station, WUGA, played hour-long lectures by Martin Luther King Jr. and Alan Watts, and we listened reverently while mucking the stables, sewing curtains for the trailer from found vintage fabrics; boiling vats of soybeans to make vegan milk and soyburgers from our battered copy of the New Farm Vegetarian Cookbook.

We left that gig after the barn manager, a white woman, refused to curb her use of the n-word despite our repeated requests, and the farm owner—a white man from “Rhodesia” (the former apartheid state in what is now Zimbabwe) who had a horse named Napoleon—declined to intervene.

We traveled in my maroon stick-shift Honda civic to Nova Scotia, and then to the Great Lakes, camping in fields and working the harvest until winter set in, and then we moved to Boston, where we rented an attic room from a young indigenous woman, a survivor of adoption and abuse, who drank herself into a mean, silly stupor most days. When we got home from our mornings at the coffeeshop (Duncan) or nights at the restaurant (me), we tried to sneak up to the attic as quietly as possible so as to avoid any projectile, verbal or material, that she might launch down the stairs from her perch at the kitchen table. At the top of the attic steps, I made an office in a dormer alcove, fitting a small desk under a window looking out over the Massachusetts Turnpike and the Charles River.

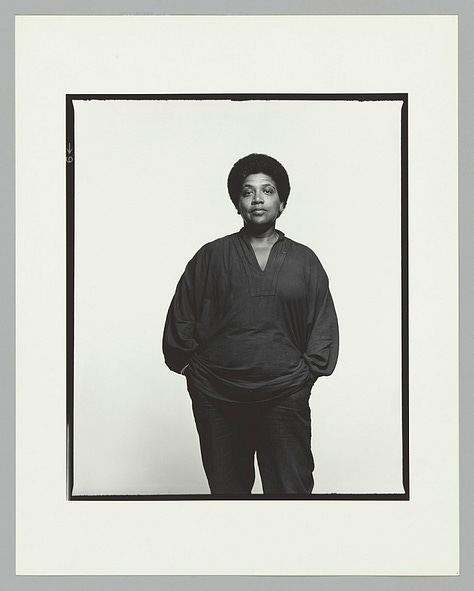

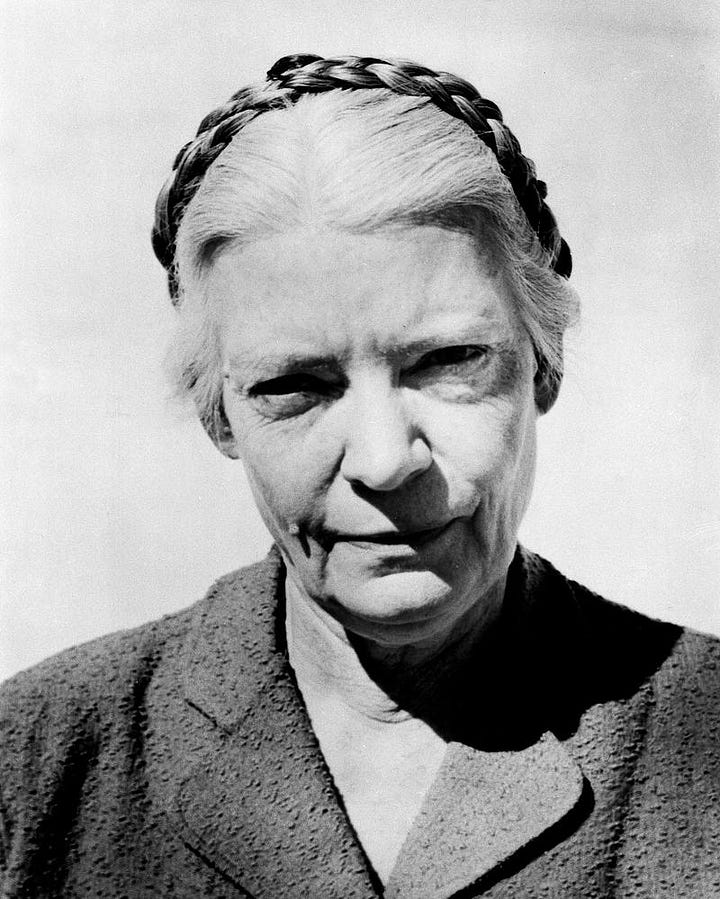

This office was the headquarters of my one-woman revolution, where I took home volunteer copywriting work from the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective and did homework for the non-profit grant-writing class I took in the ground floor of a little brownstone off of Massachusetts Avenue. On the walls of my tiny alcove, I tacked a collection of postcards of feminist icons: Fannie Lou Hamer, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Toni Morrison, Dorothy Day.

By the time we found and joined the community at Haley House, one of the houses of hospitality founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin’s Catholic Worker movement, I was ready to give myself over fully to the vision of (to borrow from an old Industrial Workers of the World slogan) building a new world within the shell of the old.

I think about these icons to whom I looked in my first formative years as an activist. What would they do with this moment? Who would Dorothy Day vote for? No one, as it turns out. According to her biographer, John Loughery:

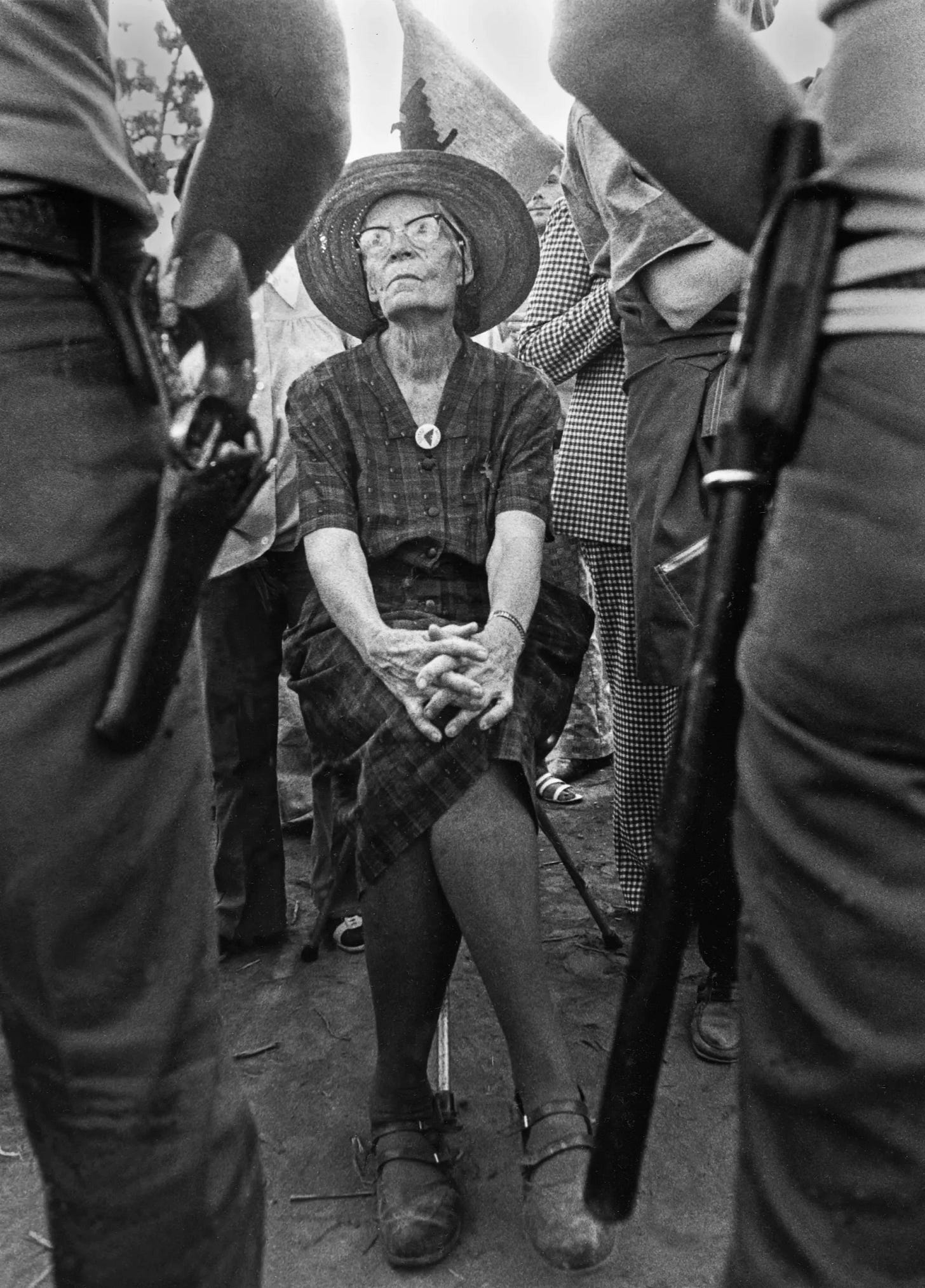

Dorothy Day was fundamentally an anarchist…. She never registered with any party and, while she was not a Communist, refused to repudiate those Marxist governments that displayed any genuine concern for the poor. She was arrested and brutalized in jail in D.C. after demonstrating in front of the White House for suffrage in 1917, but once women gained the right to vote, she never voted. She didn’t believe that voting for one party or another would make a significant difference in the ways that mattered to her. Wilson was a lying warmonger, in her view; the Harding-Coolidge-Hoover years were anathema to her from start to finish; she never thought well of FDR (his refusal to support an anti-lynching bill and his internment of the Nisei were unforgivable in her eyes nor did she think the New Deal was all that it was cracked up to be), and Truman through Nixon—Democrat or Republican—just led to more Cold War rhetoric, bigger Pentagon budgets, more nuclear weapons, more support for dictatorships abroad, needless deaths in Korea and Vietnam, out-of-control consumerism and abuse of the environment. She was probably right.

You or I can disagree with her choices but we can’t say she was inconsistent: Dorothy Day was unyielding in her practice of principled non-violence, non-cooperation with empire, and radical solidarity with the poor and oppressed, and she recognized that it is not the established institutions of governance and patterns of social behavior that will redeem us, but love:

“We have all known the long loneliness and we have learned that the only solution is love and that love comes with community,” she said.

I feel that long loneliness. I know what it feels like to be a person set apart: to believe that I am uniquely fucked up and broken in a way that others will not accept or understand, beyond the pale, to know that some of my life experiences have been really extreme, and I am extreme in some ways because of them. I didn’t survive a literal earthquake like Day, but I’ve rarely stood on solid ground.

The hell of our old roommate in Boston is not separate and different from the hell of my client, or the hell of the cat she wishes she could save, or the hell of the wage slavery she faces, or the hell of the unhoused, or the hell of the starving children of Palestine. The location where all of these interwoven oppressions are replicated and reinforced—like a virus, like an algorithm—is in our interpersonal relationships, one to one. The family, the workplace, the clinic, the checkpoint, the barn, the street. The established institutions of governance and patterns of social behavior. That is where racism happens, it’s where patriarchy is upheld, it is where all forms of harm take place: in relationships, and therefore it is the location where all of these systems can be challenged, broken down, disentangled, healed, transformed.

It can be easy to feel sorry for ourselves, to calculate an arithmetic of despair and loss and grievance; but the truth is, in the words of my late spiritual teacher and dear friend Glo: we are so fucking lucky. We are alive at the end of this world, and we get to midwife the world that is being born. We get to tell the truth and shame the devil, we get to let it all go, throw it to the sea, start anew, keep it moving.

We know that our world is breaking, we know that we can’t go on like this anymore. But the remedy is in the poison: hell is other people, but so is paradise. I feel it every day in the streets, in the community that grows deeper and stronger and more beautiful and more resolute every day, as we fight to bring about the future where Palestine is free.

In love, in community, in each other, we find our redemption. We were made for these times, and we have work to do: we have a paradise to build in hell, a new world in the shell of the old.

Home + The World is a weekly newsletter by Jodi Rhoden featuring personal essay, recipes, links and recommendations exploring the ways we become exiled: through trauma, addiction, oppression, grief, loss, and family estrangement; and the ways we create belonging: through food and cooking, through community care and recovery and harm reduction, through therapy and witchcraft and making art and telling stories and taking pictures and houseplants and unconditional love and nervous system co-regulation and cake. All content is free; the paid subscriber option is a tip jar. If you wish to support my writing with a one-time donation, you may do so on Venmo @Jodi-Rhoden. Sharing

with someone you think would enjoy it is also a great way to support the project! Thank you for being here and thank you for being you.⚔️❤️ Jodi

Another amazing essay. Stopped me from breathing a couple of times. There is much to sit with in this analysis. The reminder that In times of devastation we come together with selflessness. I saw it when my community was devastated by hurricane ida. We are living in a horrible time; I’m holding on to the hope that we will heal. Another theme is that so few know of the deep poverty in American life. Michael Marmot describes how living in poverty up against affluence compounds the burden of poverty. That is what we experience in Philadelphia. And it is heartbreaking and intolerable. White men standing alone, governing insolently brought us to this moment. Change is gonna come…

Well put. To paraphrase, “They were the worst of times, they were the best of times”. The one gift/burden of having earned my degree in History is knowing that Mankind has not changed much. It has always been difficult, dangerous and also, glorious. My perspective on the world depends on where I focus my attention. Many are racists, many are angels, all are human. We learn to the extent that we keep our minds open. A revolution is always coming, moments of peace fleeting. Personally, I have been given a second chance at life. The best I can do some days is to be kind. I love reading your essays. Please continue.